Improving Zoning Together: Available Groceries & Healthcare Outcome

co-authored by Lydia Lo, Senior Research Associate, Urban Institute

Improving Zoning Together: How do zoning and land use affect access to groceries and healthcare?

Metropolitan Planning Council (MPC) and the Urban Institute are conducting research on how zoning and land use impact Chicago’s neighborhoods and residents from an equity, sustainability, and public health perspective. We are assessing and quantifying the extent to which zoning and changes in zoning have contributed to Chicago’s long-standing inequities across seven priority outcomes: affordable housing, strong business corridors, limited pollution exposure, accessible public transit hubs, productive land use, available groceries and healthcare, and mitigation and adaptation to climate change.

This work on healthcare and groceries is part of a larger blog series titled ‘Improving Zoning Together‘, which explores our research findings based on each of the research outcomes.

In this blog, we provide a summary of our research into 1) how healthcare and groceries are distributed across the City of Chicago, 2) how zoning for healthcare and groceries, as well as land use, differs across Chicago, 3) and how healthcare and groceries availability are related across Chicago neighborhoods. Healthcare availability and groceries availability were investigated separately.

How is healthcare and grocery availability distributed across the City of Chicago?

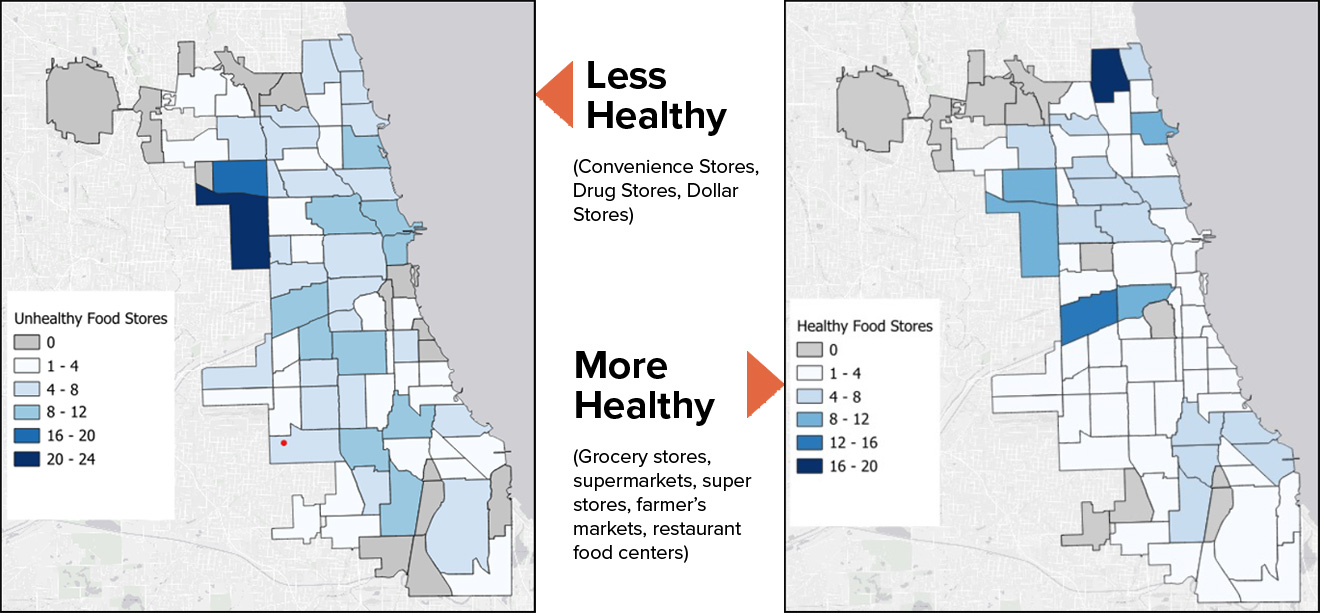

Grocery Access: We used data on grocery stores and grocery store access from USDA to better understand grocery availability in Chicago. While all neighborhoods have at least one food store, slightly more food stores are found on the north and west sides, compared to the south side. There are particular clusters of food stores in neighborhoods with strong ethnic and immigrant identities, such as Chinatown, Little Village, and Little India. Community areas have an average of eight food stores, which can come in the form of a grocery store (small store, usually independent), supermarket (traditional store), or super store (large grocery store, such as a Costco). Stores on the northside have access to more healthy food (Figure 1).

Poor grocery access for low-income households is most strongly correlated with racial tract demographics, especially segregated Black communities, but higher shares of business zoning are still related to better grocery access. Healthy foods access is dependent on factors outside of zoning.

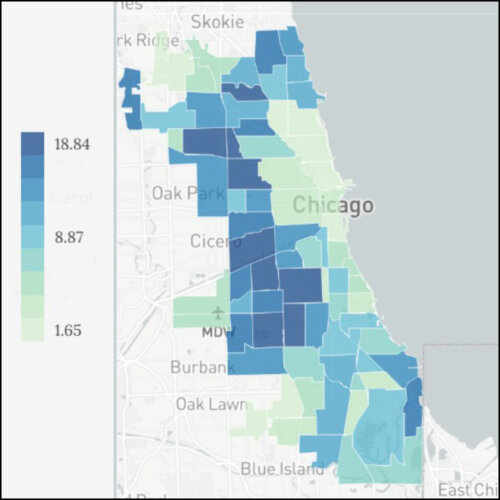

Healthcare Access: We used several different measures to better understand the healthcare access landscape in Chicago —primary care clinics (those designed to provide care to underserved populations), outpatient care locations, hospitals and pharmacies, self-reported primary care access, and health insurance. Overall, geographic access to primary care and outpatient clinics follows wealth and diversity: the wealthiest and most diverse tracts had the best access. Mental health and pharmacy sitings also follow this trend.

Primary care clinics are primarily located outside of the Loop, with clinics denser in north and western neighborhoods. Primary care access is more sparse in southern neighborhoods. Major hospitals, however, were relatively evenly dispersed (Figure 2). While facilities may be present, the number of adults who report that they have at least one person they think of as their personal doctor or health care provider is highest in northern community areas and lowest in near and far south neighborhoods (Figure 3).

Figure 2

Chicago HHS hospital and primary care clinic locations

Figure 3

Primary care access better in Chicago’s northern neighborhoods

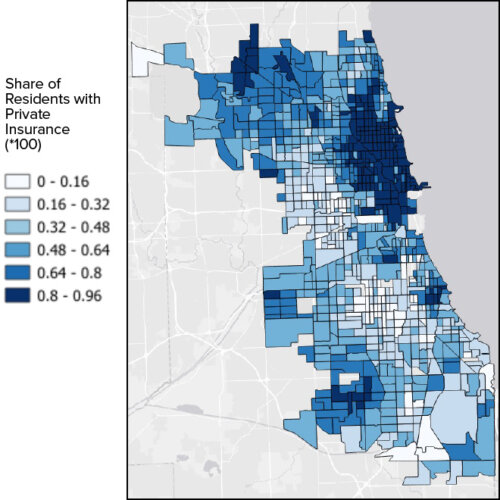

Given that healthcare access is related to health insurance, data shows that health insurance coverage type correlates with wealth. Uninsured populations ring the outer edges of the city, and cluster around the southwest side of Chicago (Figure 4). Tracts with the highest share of residents who have at least one type of private insurance are clustered in the Loop and near north. Physician and outpatient access are correlated most strongly with private insurance coverage (Figure 5).

Figure 4

Uninsured populations ring the outer edges of the city

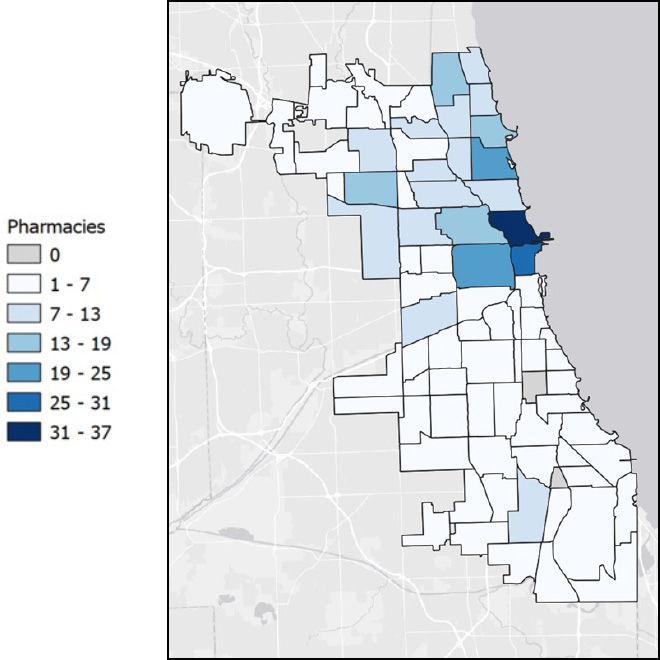

Full-spectrum healthcare access includes pharmacy access. Most community areas have at least one pharmacy but, as with healthcare clinic access and health insurance coverage patterns the South side has lowest concentration of pharmacies and most community areas with no pharmacies (Figure 6). Healthcare care and pharmacy access are dependent on factors outside of zoning.

Figure 6

Pharmacy locations by community area

What does zoning for healthcare and grocery stores—and corresponding land use—look like in Chicago? How does it compare to other municipalities?

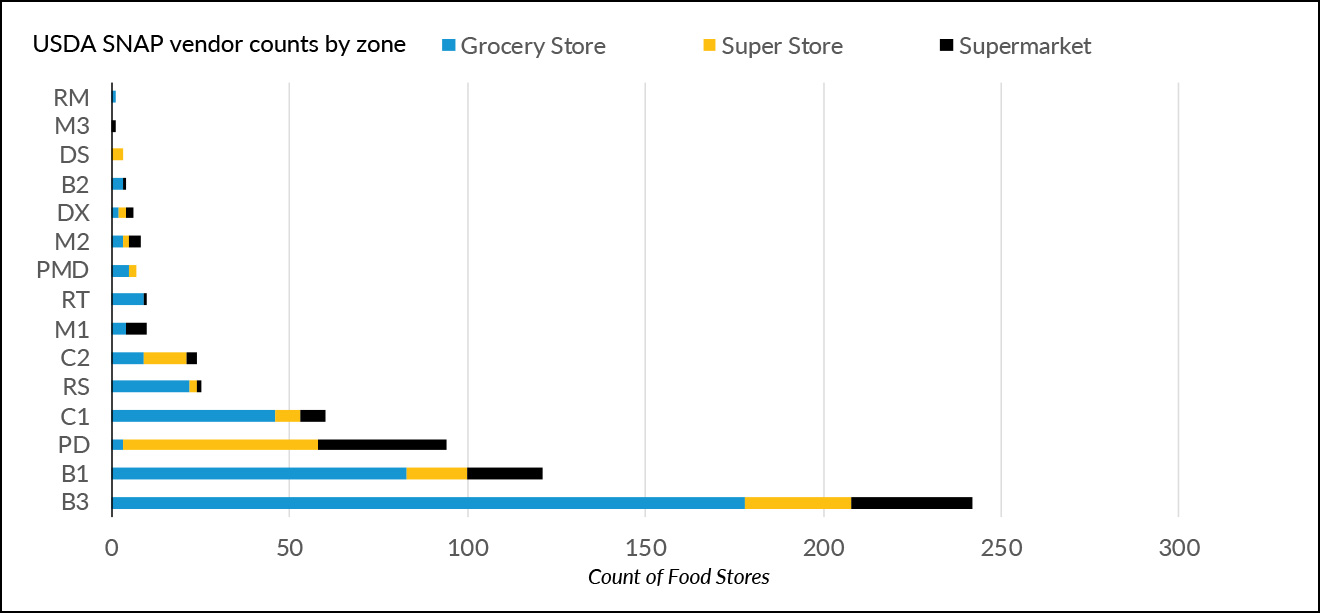

Grocery Access: Food and beverage retail sales allowed by right in all B and C zones. Most healthy food stores are in B3 zones while super stores and supermarkets are mostly located in PDs (Figure 7). Chicago’s zoning ordinance doesn’t incentivize grocery location in any specific zones. Unlike other jurisdictions, Chicago’s zoning ordinance does not prioritize grocery stores as a use in overlay districts (e.g., Tulsa, OK), require grocery stores in certain districts (e.g., Tybee County, GA), offer density bonuses to developments that have grocery stores (e.g., Carteret County, NC), or explicitly permit and encourage healthy grocery access in zones (e.g., Madison, WI).

Figure 7

Most healthy food stores are in B3 zones while super stores and supermarkets are mostly located in PDs

Note: This excludes specialty stores, pharmacies, corner stores, convenience stores, and farmers markets

Healthcare Access: Medical Services are a by-right permitted use in B, C, and D zones (except DR). Government-operated health centers are permitted by special permits in RT-4, 4.5, 5, and 6 zones or higher density residential areas. Currently, no incentives are given to locate medical services in any area.

What do zoning trends mean for Chicagoans’ access to healthcare and groceries?

Grocery Access: Poor grocery access for low-income households is most strongly correlated with racial tract demographics, especially segregated Black communities, but higher shares of business zoning are still related to better grocery access. In an earlier blog post, MPC found that business zoning is correlated with market activity. Additionally, we found that medium-density zoning was associated with more healthy food access—the greater the share of lowest and highest density zoning, the fewer the healthy food stores.

Healthcare Access: The research suggests that rather than being driven by zoning, access to healthcare is closely tied to non-zoning factors such as insurance and income. Physician and clinic access is positively correlated with wealth, high-density and zoning and Planned Developments, and white resident concentration. Proactive planning and zoning changes could have an impact on encouraging more mixed-use development and lowering barriers for new businesses that advance the health of residents.

Proactive planning and zoning changes could have an impact on encouraging more mixed-use development and lowering barriers for new businesses that advance the health of residents.

Key Takeaways

Healthcare and grocery sitings are inequitably distributed across Chicago. Although zoning does not appear to be responsible—with other factors like wealth, tract demographics, and health insurance access all highlighted in our analyses—zoning policy changes can help residents live healthier lives in all neighborhoods. Chicago’s zoning ordinance is not being used to incentivize or influence the geographic location of these services that are traditionally associated with health in non-white racially or ethnically concentrated communities with lower levels of geographic access. As MPC and its collaborators continue to assess the many impacts of zoning in Chicago, we are exploring policy recommendations that could be a mechanism to proactively realign the zoning code in ways that respond to conditions such as food or healthcare deserts.

Related Reading

Blog Series: Improving Zoning Together

- Improving Zoning Together: Introductory Blog

- Limited Pollution Exposure Outcome (Part 1 of 2)

- Limited Pollution Exposure Outcome (Part 2 of 2)

- Affordable Housing Outcome (Part 1 of 2)

- Affordable Housing Outcome (Part 2 of 2)

- Strong Business Corridors Outcome

- Accessible Public Transit Hubs Outcome

- Available Groceries and Healthcare Outcome

- Mitigation and Adaptation to Climate Change Outcome