How does the RTA’s transit reform proposal align with the PART recommendations?

Multiple studies have concluded that for Northeastern Illinois to have a sustainable transit system for the future, governance reform is needed along with increased funding. While it is positive to see RTA advocate for governance reform at its August 15, 2024 board meeting, its reform proposal does not adequately address the transit governance recommendations in the 2023 Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning (CMAP) Plan of Action for Regional Transit (PART), a comprehensive report on transit funding and governance that was commissioned by the General Assembly. The RTA’s reform package1 also falls well short of the reforms in the Metropolitan Mobility Authority (MMA) Act (SB 3937), which tracks CMAP’s transit governance Option #1. The RTA’s proposal is a missed opportunity for meaningful consideration of bold and exciting ideas for a truly reformed structure for delivering the kind of reliable and equitable public transit residents, employers, and service providers like schools and hospitals in the Chicago region want and deserve.

1 The RTA reform package is found on slides 32-35 of the August 15, 2024 RTA Board packet.

Background

First, let’s review why substantial reform is needed, as has been discussed and well documented for at least the past three decades.

A 1994 report on the future of transit by MPC resulting from a regional task force and funded by the RTA, said:

“Financial restructuring and service expansion are more likely to succeed if the region tackles three difficult issues that contribute to the current mobility problems:

- Land use should support transportation investments

- Public funds for transportation should provide incentives to achieve regional goals

- Regional governance structures should be reworked to be more responsive to changing transportation needs.”

A 2007 report by the Office of the Illinois Auditor General concluded: “The General Assembly may wish to consider several statutory changes to address mass transit in northeastern Illinois:

- Change the Governance Structure. Such changes could range from enhancing the RTA, e.g., planning, reviewing budgets, finance, coordination of fares, performance measurement and oversight of operations) to centralizing governance.

- Review the funding formula. Service boards are funded by sales taxes that are distributed by statutory formula, which has remained unchanged since its inception in 1983.

- Review the RTA Board membership. The current allocation of RTA board members is not consistent with the population distribution of the 2000 federal census.”

The 2013 Northeastern Illinois Governor’s Task Force Report recommended:

- “Creation of a single integrated transit entity for the region.” The report provided an example of how the region might create a new governing board to replace RTA, CTA, Metra, and Pace, under which the service boards would become operating units.

- Creation of a regional transit plan and develop regional performance measures to assess progress toward implementing the plan.

The 2014 Eno Center for Transportation Report concluded:

- “Choose independence or choose consolidation—you cannot have both. Numerous interviewees in the Chicago region agreed that RTA either needs to be strengthened or eliminated. Either one would be preferable to the current situation where the RTA is just strong enough to be an obstruction, but too weak to have any real planning influence over the region.

- It is shortsighted to have no state involvement in transit when transit has such a large impact on the economic success of the state.

- Having one entity holding the purse strings is a necessary, but not sufficient means of bringing regional transit entities together effectively.”

The 2013 Delcan Report commissioned by the RTA concluded:

- “The current institutional and financial structure used for transit in Northeastern Illinois is flawed. The funding formulas are complex, out of date (some rules have been unchanged for thirty years), and rigid.

- RTA does not have the necessary authority to support the planning and decision-making process called for in current legislation (the RTA Act), resulting in an effort that is involved, argumentative, and often unproductive.

- No other major metropolitan region in the US has selected a similar institutional arrangement.

- The current supermajority requirement to approve financial plans and other key measures makes it possible for relatively small groups to exercise veto power over key decisions.”

The PART Report and RTA’s Reform Package

CMAP’s 2023 PART Report documented the weaknesses of the current governance structure, which it described as “layered and complex” and noted that “past recommendations made by transit advocates to increase regional coordination for planning, policy, and funding allocation remain unfulfilled.”

CMAP’s PART Report observed with approval how other regions such as New York and San Diego have evolved from fragmented transit governance structures to integrated regional transit authorities (pg. 111).

CMAP advanced two transit governance reform options. Option #1 achieves the integrated regional agency end state by creating a single regional transit agency with full operating responsibilities and a single board. Option #2 would invest more powers in the RTA (or a successor) and its board but keep the three existing service boards—CTA, Metra, and Pace–and their separate boards of directors intact:

Ultimately, it was assessed that integrating RTA and the service boards into one regional transit agency has great potential to support the implementation of PART recommendations and to address historic challenges. However, with sufficient provisions, empowering the regional coordinating agency while maintaining the service boards as operating agencies is also a strong option (pg. 105).

The MMA Act bill (SB 3937) advances an Option #1 solution. It would consolidate CTA, Metra, and Pace into the MMA, making them operating divisions rather than standalone agencies with their own boards. RTA and its functions would be folded into the MMA too. Here is a summary of the MMA

In a July 31, 2024, webinar, RTA staff stated that RTA opposed an Option #1 solution and advanced an RTA reform proposal. Staff briefed the RTA Board on the reform proposal on August 15, 2024. That proposal would give the RTA expanded powers in three areas:

- Service Standards: RTA sets regional standards for frequency of service and service boards report on their performance relative to those standards

- Fare Policy: More RTA decision making power and oversight over the fares set by the service boards

- Capital Planning: RTA provides more capital planning vision and prioritization rather than responding to service board capital project proposals

These proposals have yet to be fleshed out in publicly accessible proposed legislation or otherwise. We can only hope that RTA’s reform ambitions will grow over time.

An initial question, beyond the scope of this post, is why the RTA believes it currently lacks the power to do these things under its existing statutory authority in the RTA Act. After all, the RTA has transit planning powers, and it must approve the operating budgets and capital programs for each of the service boards. These existing powers would seem to give RTA substantial leverage to establish regional service standards, condition approval of operating budgets on service board compliance with a regional fare policy, and require earlier and more robust information flows about proposed capital projects and their costs from the service boards.

RTA’s package does not meet CMAP’s governance reform principles

Beginning on page 101 of the PART Report CMAP lays out “baseline principles for reform.” These principles apply to both Option #1 and Option #2 governance reforms. The RTA’s proposed reform package falls well short of these principles:

- Prioritize regional goals and decision making instead of statutory funding formulas: CMAP recommends that the current fixed statutory transit funding allocation formulas be rolled back so the Chicago region can more effectively allocate funding to meet regional needs and goals. The RTA’s reform does not address this CMAP recommendation.

- Grant more regional discretion over how funds are allocated: CMAP recommends that after baseline needs are funded substantial additional funding should be allocated through a competitive grant or other performance-based allocation process. The RTA reform package does not address this CMAP recommendation.

- Implement the regional decision making and oversight necessary to advance system goals: CMAP recommends that some transit functions such as service levels and fare policy should be handled at the regional level by the regional agency. RTA’s reform package is consistent with this recommendation. CMAP goes on to recommend that “the regional agency should set and monitor performance measures for regional priorities and operational efficiencies… [it] should lead funding allocation strategies to achieve baseline operational funding, implement capital projects, and advance innovation in the face of changing conditions.” RTA’s reform package does not address this CMAP recommendation for performance measures backed by funding allocation consequences.

- Reduce the farebox recovery ratio requirement: CMAP makes a compelling case against retention of the so-called farebox recovery ratio, at least at its current level. The farebox recovery ratio requires the service boards to raise an assigned percentage of their operating costs from fare revenue. CMAP points out how this requirement distorts incentives and pits service boards against each other. RTA’s 2024 Legislative Agenda, adopted in November 2023, does call on the General Assembly to “[e]liminate the current 50 percent farebox recovery ratio to provide more equitable service that connects people to opportunity.” That recommendation is not included in RTA’s more recent reform proposal that is the subject of this post.

- Empower the regional agency to look beyond the fare recovery ratio and set updated performance metrics based on regional strategies and goals: CMAP recommends that “Governance reform should enable the regional transit agency to more effectively set, monitor, and adjust performance metrics to align with strategic plans, service standards, and regional and state climate and equity goals.” The RTA reform package does not address this CMAP recommendation.

- Reform the Regional Transit Board: CMAP makes a number of recommendations relating to the transit boards in the region:

- Design board appointment and voting structures to advance regional progress while building local consensus;

- Integrate more regional perspectives;

- Provide a greater role for the state, especially as it increases its funding support;

- Ensure that regional board membership reflects population, ridership, and funding sources;

- Appoint board members with relevant and diverse experiences; and

- Provide avenues for local input.

The RTA reform proposal does not address any of these CMAP recommendations relating to transit board governance. It maintains the current governance status quo, which gives suburban Cook County and the collar counties no representation on the CTA board, limits City of Chicago appointees to only one each per Metra and Pace boards, and gives the State of Illinois no appointments to the RTA, Metra and Pace boards even though the Governor appoints three of the seven CTA board members. The RTA’s reform package does not address these representation anomalies relative to the transit services provided and needed and the contributions of riders and revenue by each of the six counties that make up the RTA. See MPC, Taking PART in the Region’s Transit Governance Conversation (2024) and The Transit Governance Model in Chicago: An Outlier (2024).

The MMA Act tracks CMAP’s governance reform principles

In sharp contrast to the RTA reform package’s lack of alignment with CMAP’s recommended governance reform principles, the MMA Act tracks those principles. The Act abolishes the farebox recovery ratio and the fixed statutory funding allocations among the service boards, giving the MMA the authority to allocate funding consistent with service standards that reflect the region’s transit needs and goals and treat like communities alike. By consolidating the transit service providers into one agency, under one board, the MMA Act ensures that CMAP recommendations for things such as performance metrics can be implemented without the institutional risks of non-cooperation, non-compliance, and lack of shared goals that is inherent in the current fragmented institutional structure with its multiple independent agencies and boards with skewed director representation.

The MMA Act also addresses CMAP’s recommendations relating to the structure and operation of the regional transit agency board. The Act gives the State of Illinois representation on the MMA Board. It includes provisions that cultivate a more regional perspective by MMA directors. These include allowing appointing agencies to appoint directors from anywhere in the metropolitan region, rather than being limited to residents of just their subregion and giving the public a voice in the director selection process. In addition, a variety of community representatives are given a non-voting seat on the MMA Board, with full rights to participate in Board proceedings. The Act explicitly requires MMA directors to take a regional perspective in their decision making.

The MMA Act lays the foundation for performance metrics. For example, it requires MMA directors to report their usage of the public transit system they oversee. The Act authorizes the MMA Board to establish ridership requirements for MMA executives and staff. It authorizes using performance-based compensation systems for MMA executives and even staff. The Auditor General is directed to do periodic performance audits of the MMA to help inform each iteration of the MMA’s strategic plan.

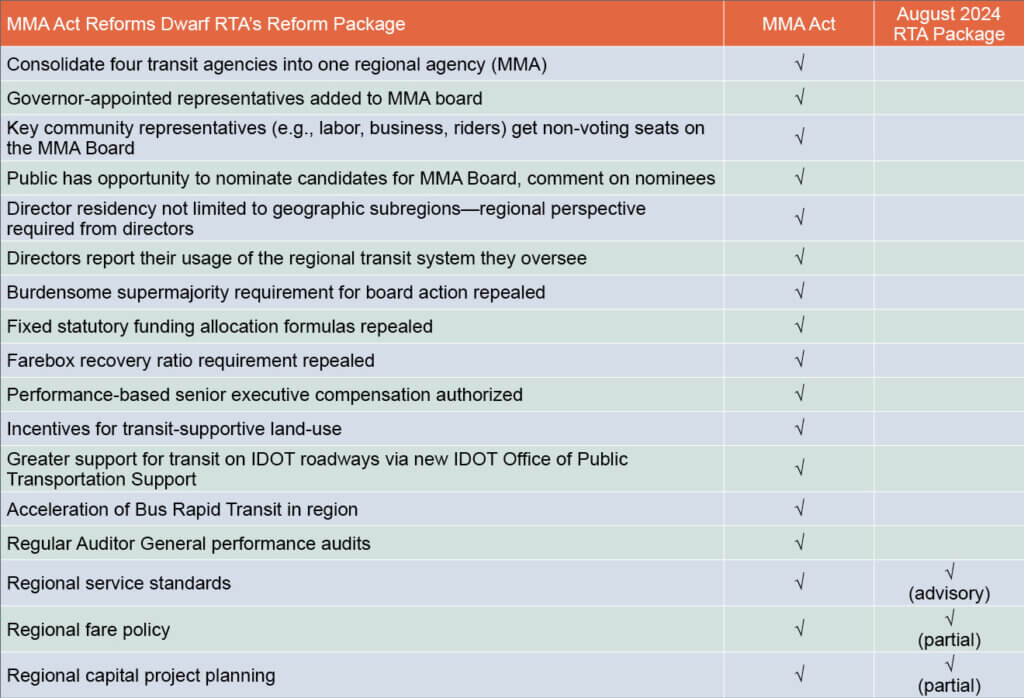

The differences between the suite of reforms in the MMA, which track CMAP’s recommended governance reform principles, and the RTA’s modest reform package, are illustrated by this side-by-side comparison:

As CMAP documents in the PART Report, and as other studies have concluded, the current transit governance structure is suboptimal. The Eno Transportation Center observation a decade ago in Getting to the Route of It: The Role of Governance in Regional Transit (2014) is still applicable today:

The RTA is a peculiar hybrid of a regional transit organization and a quasi-MPO. Like a regional transit organization, it controls transit funding for the region. But like most MPOs, it actually winds up having very little power to enforce funding decisions. The inherent problem is that RTA occupies an ambiguous middle ground where it is powerful enough to create challenges and bureaucracy, but not powerful enough to be productive in pursuing regional goals. [pg. 20]

Past reforms have had little substantive impact

We should be wary of more efforts for incremental reforms that will not deliver results. Past reform efforts to invest the RTA with greater powers have had limited results. The reforms of 2008, while hard-fought, were not enough and were not implemented thoroughly. In 2011 the General Assembly amended the RTA Act and directed RTA to “develop and implement a regional fare payment system” by 2015. While significant progress has been made, as of 2024 this integrated fare payment system has yet to be fully implemented. Likewise, RTA has the existing authority to review and reject if necessary proposed service board operating budgets and capital programs, but it has failed to exercise these powers to achieve the objectives that it claims its reform package will deliver. If RTA cannot effectively use this existing power to implement regional operating and capital priorities it is hard to see how giving it line-item veto power will do the trick. This is especially so since the RTA’s supermajority requirement allows a bloc of director appointees from any subregion to block RTA’s use of its service board budget review powers to advance regional priorities supported by a majority of directors. The current supermajority requirement allows a minority bloc to veto measures supported by two-thirds of the directors. Yet, the RTA reform package ignores CMAP’s recommendation to change the RTA Board supermajority requirement; in contrast, the MMA Act abolishes that requirement.

What will it take to execute meaningful reforms?

There is a saying that the strongest force in government is inertia. This points to the institutional risk arising from the “culture,” division of responsibilities, and settled expectations that have formed among the RTA and service boards over the past 40 years. The notion that the elements of the RTA’s reform package are enough to effectuate meaningful improvements in the region’s transit governance and operations is naïve in the face of these deeply rooted norms.

The MMA Act attempts to mitigate the risks associated with transit governance today in the Chicago region by transforming the current transit service providers with their separate boards and loose RTA oversight into operating divisions of a single agency with a single governing board. The MMA also lays out a multi-year transition period where the MMA Board plays an outsized role in implementing the reforms mandated by the General Assembly. The resulting operating divisions of the MMA will be horizontally and vertically integrated under the direction of a single board that can be held accountable for delivering an improved regional transit system.

As critics have pointed out, there are risks associated with large, regional transit agencies, such as shortchanging riders in the urban core and being deaf to specific local needs, e.g., Jarrett Walker, Chicago Region: Rethinking Both CTA and Pace (2024). The greater risk, however, is perpetuating the 40-year status quo, as the RTA’s proposed reform package clearly does, and continue our “peculiar hybrid” of fragmented transit governance and a weak regional transit agency.

While important that we not minimize the challenges associated with implementing the MMA Act reforms, it is useful to remind ourselves that our predecessors took on similar challenges when the formed the CTA out of several private transit companies in 1945, established and radically reformed the RTA in 1973 and 1983, and built out Pace and Metra from a patchwork of transit operators. Other regions have succeeded in creating truly regional transit authorities. It is time for our region, with the State’s assistance, to reform how we manage and fund public transit in the Chicago region.

Conclusion

The RTA’s proposed reform package is a recipe for more of the same. That reform package fails to meet most of CMAP’s recommendations to the General Assembly for the guiding principles for needed transit governance reforms in the Chicago region. The RTA’s package falls well short of the reforms in the MMA Act and of what is needed to warrant an additional $1.5 billion in operating funds annually to substantially improve transit services throughout the region.