Water Infrastructure Workforce: the Racial and Gender Equity Imperative

Illinois needs to invest $27.4 billion in the coming decades to ensure clean drinking water and resilient, sustainable stormwater and sewer systems, according to estimates from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency[1]: $20.9 billion will need to be invested in our drinking water treatment plants, water storage facilities, transmission lines, and other drinking water infrastructure by 2040; and $6.5 billion will need to be invested in upgrading sewer treatment plants, replacing sewer mains, building green infrastructure to manage stormwater, and otherwise meeting the requirements of the Clean Water Act.

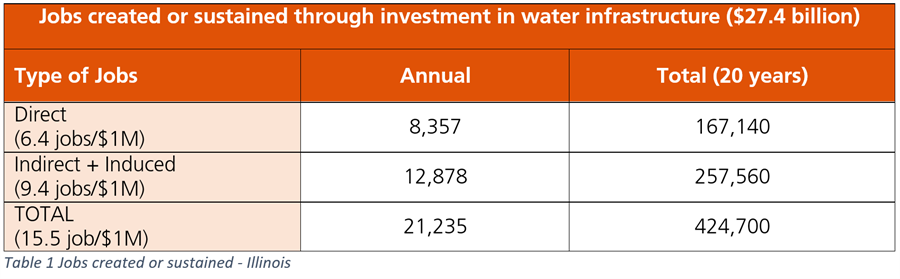

Economists generally agree that all this needed investment in water infrastructure will lead to strong job growth and economic output. A 2017 Value of Water paper estimates that 6.1 direct jobs and 9.4 indirect/induced jobs are created for every million dollars spent in water infrastructure. This means Illinois could see 424,700 total jobs created over the next 20 years (see Table 1).

Two critical and related opportunities must be seized to ensure the health of our water workforce.

First, we will likely need to grow the water workforce to meet growing demand. Nationally, a combination of turnover and “future growth in the water sector is projected to lead to about 220,000 occupational openings – on average each year.” In other words, due to retirements, professional mobility, and an increased urgency to deal with new types of infrastructure issues like the replacement of lead service lines, there is growing demand for water infrastructure workers.

Second, there is a need to ensure racial and gender equity in the water workforce. Nationally, people of color are under-represented in the water infrastructure workforce, especially in the sector’s higher paying jobs like executives, construction managers, and civil engineers: Black, Hispanic, and Asian workers constitute 33 percent of the water workforce; yet they make up less than 20 percent of the sector’s higher paying jobs. Women make up less than 15 percent of the sector nationally, and less than 2 percent of the sector’s construction and heavy equipment operating jobs, which tend to have higher wages than the sector’s office jobs, of which women constitute 85 percent-plus of the workforce. Deliberate and targeted outreach will be needed to ensure people of color and women are accessing the breadth of jobs and pay scales available in the water sector.

The racial equity imperative is intensified by the reality that, while people of color are nationally under-represented in the highest paying sectors of the water workforce, they are too frequently over-represented in communities suffering under the weight of crumbling or outdated infrastructure. Take, for example, lead service line replacement in Illinois[2].

As Tara Jagadeesh and I have documented, although lead service lines are distributed across the state, they disproportionately affect Illinois communities where people of color live: Illinois’ Black and Latinx residents are twice as likely as white Illinoisans to live in one of the communities that contain nearly all of the state’s lead service lines.

Now is an important moment to cultivate a diverse water workforce in Illinois: Not only has the State committed to replacing its lead service lines, but we are poised to receive billions of dollars in federal drinking water and wastewater infrastructure funding through the 2021 Bipartisan Infrastructure Law. While the Clean Water Workforce Pipeline program established through state legislation in 2019 is a promising start, that program needs to be funded and developed to live up to its potential. We must ensure there is a thriving, diverse workforce who can repair, maintain, and upgrade our critical water infrastructure for present and future generations.

In 2021, the State of Illinois adopted a law requiring the replacement of all lead service lines throughout the state. This will require decades of work and billions of dollars in investment. People of color, who have disproportionately suffered the damage of this toxic infrastructure, must at a minimum be deliberately included in the economic benefits that will follow from solving this problem.

[1] 27.4 billion is likely an under-estimate: Some increasingly urgent needs and realities will likely push this number higher. For instance, U.S. EPA’s estimate only partially accounted for the cost of remediating notable drinking water contaminants like lead and PFAs. See Drinking Water Infrastructure Needs Survey and Assessment (epa.gov), p. 26.

[2] Racially inequitable provision of infrastructure is likewise demonstrated in flooding disparity. See https://www.cnt.org/sites/default/files/pdf/FloodEquity2019.pdf.