The 15-Minute City: How Close Is Chicago?

Before cars, most city-dwelling Americans could reach the essentials by foot or bike within 15 minutes. As this old idea generates new buzz in the urban planning community, we investigate how far Chicago has strayed from that pedestrian-friendly norm.

On July 15, C40, the international consortium of global cities committed to fighting climate change (of which Chicago is a member), released a policy agenda to guide cities toward an equitable and sustainable COVID-19 recovery. As reported in CityLab, the report contained an interesting proposal that’s recently been popular in urban planning and design circles: the “15-minute city,” a concept in which essential goods, services, and destinations should be accessible to all city residents within a 15-minute walk or bike ride.

This is not new. Before trains and cars made high-speed transportation possible, all cities were 15-minute cities. Each neighborhood functioned as a self-contained urban ecosystem where you could get everything you needed using the only mode of transportation you likely had available: yourself. Over the decades, auto-oriented planning increased the distances between our homes and destinations. Economic forces and racist planning practices further eroded the historic densities of American communities.

But not every neighborhood has been impacted equally. As my colleagues Christina Harris and Shehara Waas showed in a recent Data Points blog, access to necessities such as grocery stores are inequitably distributed, following familiar patterns of segregation. Reduced access to essentials has very real impacts on community health, made all the more immediate by the global pandemic.

Building on my colleagues’ work, I wanted to know how access to other essential destinations varies across the city. If Chicago wants to become a 15-minute city, how close are we now?

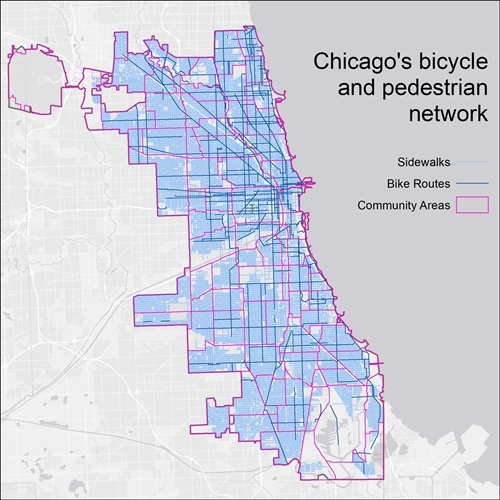

Our bicycle and pedestrian network: Disparities between the North and South Sides

The first step to assessing how close Chicago is to a 15-minute city is defining our network of pedestrian and bike infrastructure. Here’s how we did it:

Map all streets with a sidewalk on at least one side. This is the bare minimum definition for walkability and definitely doesn’t guarantee access. For instance, we don’t have public data on the location of crosswalks, curb ramps, or pedestrian signals.

Map all bike routes currently designated by the Chicago Department of Transportation. These can range from simple signed routes along neighborhood streets to physically protected bike lanes along major arterials. It’s important to recognize that different riders have very different comfort levels, and may not feel safe riding on many of these routes.

You can immediately see the well-documented disparity in bike infrastructure on the North and South sides. Fortunately, Mayor Lightfoot recently announced a suite of investments including expansion of Divvy bikeshare and additional bike lanes to help close that gap. The sidewalk network is also a little more fragmented on the South Side, mainly due to the numerous industrial areas dotted throughout.

What makes up a 15-minute city?

Many cities have different definitions on the basket of destination types that collectively build a complete and cohesive neighborhood. Things that are commonly included are food, health care, jobs, recreation, education, shopping, and cultural activities. For this analysis, the list was most determined by what data was available. I chose eight different destinations to map:

- Grocery stores

- Parks

- Libraries

- Primary schools

- Secondary schools

- Hospitals or urgent care facilities

- Pharmacies

- CTA ‘L’ stations

To determine access, I used GIS to measure how far somebody could travel from each destination in 15 minutes by walking or biking. These areas are respectively called walksheds and bikesheds. Below, you can see how this process played out for one of the destination types: public libraries.

Each yellow dot is a Chicago Public Library location, and the grey areas represent the areas where somebody could walk or bike to each library in 15 minutes or less. A number of assumptions are at play here. I assumed a walking or rolling speed of three mph. This would let you travel 0.75 miles in 15 minutes. I also assumed a very leisurely biking speed of 10 mph, which gets you 2.5 miles in 15 minutes. I considered any destination that was more than a quarter mile from the closest bike route to be inaccessible by bike. Conversely, I also assumed that people would be willing to travel a quarter mile (about two city blocks) to get to a bike route.

In general, access looks good

When we layer the walk and bikesheds for all eight destination types, we can see that the majority of the city has access to at least seven of the eight destinations within 15 minutes. Most of the areas with less access are on the city edges, where residents likely have access to destinations in neighboring communities that weren’t included in our analysis. The two large areas with zero access are O’Hare and the mostly unpopulated Lake Calumet industrial area.

Safety, comfort, needs may force people to travel farther

As pleasantly surprising as these results are, they come with some very important caveats. Just because you can physically reach a destination doesn’t mean it’s safe for you to do so. The physical condition of sidewalks and bike lanes vary widely, as do compounding issues like community safety. In fact, a recent research collaboration between MPC, UIC, and Equiticity documented how people’s travel behavior is significantly influenced by many non-transportation related factors.

Just because you can physically reach a destination doesn’t mean it’s safe for you to do so.

Even if you can safely reach the closest destination, it might not be preferable for a variety of reasons. For instance, you may have a small community grocer with limited items within a block or two, but still need to travel a far distance to access a full-scale grocery store. Or you may have a neighborhood school down the street, but it’s suffering from disinvestment, so your child may commute further to a different school. Lastly, not everybody is comfortable biking in Chicago. And while rates of cycling have increased in recent years, the vast majority of people are choosing other modes.

The pedestrian accessibility picture looks different without two wheels

Building a robust network of bicycle infrastructure that’s safe and comfortable for people of all ages and abilities is a powerful tool to improve community health and the environment.

Since the reality is that most people aren’t biking for transportation in Chicago, I also created a map using only the walksheds to measure access for each destination type. Without biking as an option, the map looks drastically different. Familiar patterns emerge, with denser, resource-rich neighborhoods on the North Side consistently having higher levels of access than areas on the South Side. Many communities have access to fewer than half of the eight destinations on my list.

One of the obvious takeaways is the awesome ability of bicycles to dramatically increase access. Building a robust network of bicycle infrastructure that’s safe and comfortable for people of all ages and abilities is a powerful tool to improve community health and the environment. But for some, biking may never be a practical or appealing option. Walkability will always be the bedrock of any urban community. And while there is always room for improvement, sidewalks aren’t the biggest problem for Chicago. Cities around the world are rethinking how they plan, incentivize and approve development to make sure there’s an equitable distribution of essential services, and it’s time for Chicago to do the same. C40 has some helpful advice on that front. As this pandemic has shown, our lives may very well depend on it.