CHA Plan for Transformation — January 2005 Progress Report

Since the onset of the Chicago Housing Authority (CHA) Plan for Transformation in 1999, radical changes have occurred, both inside and outside the agency. Internally, under new leadership, the CHA has transformed itself from a 2,600-person organization in charge of multiple objectives well beyond the provision of housing (such as policing, social service delivery, and property management) to a 500-person agency whose fundamental role is as an “asset manager.” Tasks now are assigned to professional private contractors (developers, managers, nonprofit organizations, etc.) or handled by appropriate public partners (city departments and sister agencies).

Externally, during this same period, the concept of public housing has changed dramatically, greatly influenced by federal programs such as HOPE VI (created in 1992) and legislation such as the Quality Housing and Work Responsibility Act of 1998. According to these new policies, public housing no longer should be a separate stock of multi-family properties, but rather quality homes integrated within stable neighborhoods and, often, mixed-income communities. Central to this notion of stability is “access to opportunity” and the availability of quality schools, social services, job opportunities, and healthy “street life.” Consistent with this approach, the CHA is undertaking the largest housing revitalization effort in the nation.

Perhaps the most challenging goal in the CHA Plan for Transformation is the creation of 6,205 new homes within mixed-income communities that replace the troubled high-rises of the past. This process goes well beyond the demolition of 7,738 apartments (many of them vacant), the relocation of thousands of families living in those buildings, and the development of new housing and infrastructures. The outstanding question is how stakeholders can provide for the long-term viability of these communities and their appeal to families and individuals from all economic backgrounds. This vision can be realized only by building strong, healthy communities for all residents within and around each development.

Successful community-building within developments requires strategies to guarantee the coordination of property management, social services and activities, and residents’ engagement. Housing developers, property managers, service providers, and residents must pay attention to local and nationwide best practices that can help them better understand their roles and responsibilities.

This progress report focuses on the creation of opportunities in the neighborhoods around mixed-income sites — quality schools and education,1 economic development (through commerce/retail and job creation),2 and adequate parks, community centers, and recreational facilities.3 While the CHA is at the center of the Plan for Transformation, this report looks at the essential work of key partners and sister agencies.

QUALITY SCHOOLS AND YOUTH PROGRAMS

As with every healthy neighborhood, a viable mixed-income community needs quality schools and youth programs. Efforts have been made by the Chicago Public Schools (CPS), the CHA, and a number of private, public and nonprofit stakeholders to address this need.

In collaboration with the CHA and other public, nonprofit and private entities during 2004, CPS undertook a planning process for the schools of the Mid-South area,4 95 percent of which are currently on academic probation. By the end of the CHA Plan for Transformation, this area will see more than 8,000 homes (2,761 of them public housing) built as part of the Oakwood Shores, Legends South, Park Boulevard, Lake Park Crescent, and Jazz on the Boulevard mixed-income communities.5 This represents an estimated net increase of 4,313 households in the Mid-South area. There is no certainty about how many of these new households will have school-age children, but a significant increase in the current student population of 8,366 is expected.

The Mid-South Plan aims to create high quality neighborhood schools that meet the needs of all families living in the area. Participants in the process developed six principles related to the interactions between housing and schools:

- Community-centered schools should be the hubs of community revitalization — providing a range of services to all residents, before and after school hours and on weekends.

- Community-centered schools should be the hubs of community revitalization — providing a range of services to all residents, before and after school hours and on weekends.

- Communities and schools must be safe and orderly, allowing a focus on learning.

- Schools should have strong partners to support teaching, learning, and student development.

- Parents and community members should sustain school diversity.

- Schools should be marketed effectively to current and prospective residents, educators, and partners.

Building on lessons learned during the Mid-South planning process, in June 2004, the city launched Renaissance 2010, an overarching, citywide effort to create 100 new schools over the next six years. Of these 100 schools, approximately one-third will be charter schools, another third will be contract schools (in which the school district contracts with an outside entity to run the school), and another third — Performance Schools — will be run by CPS. The goal of Renaissance 2010 is not only to transform underperforming schools into quality ones, but also to give families choices when deciding on their children’s future schools. When a school reopens, children who attended previously will have the right to return, provided the school still offers the grade level the student will be entering.6

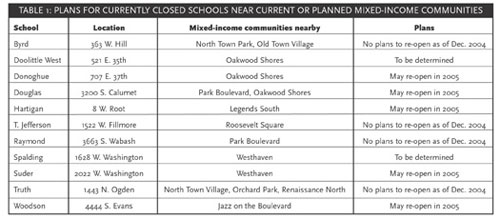

CPS plans to open six to 12 Renaissance schools by September 2005. Some of the schools in the Mid-South area will be among the first to be transformed. In years 2006 through 2010, between 15 and 20 Renaissance schools will be opened each year. Table 1 summarizes the short-term plans for a number of public schools located near mixed-income communities.

Looking ahead, issues to be addressed as Renaissance 2010 unfolds include how to coordinate the development timelines of mixed-income communities with the openings and closings of schools nearby, how to establish ongoing communication mechanisms to report on the status and progress of Renaissance 2010 to all stakeholders, and how to market these new schools to parents considering moving into the new mixed-income communities.

ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT: COMMERCE, RETAIL LIFE, AND JOBS

The overall economic health of the new mixed-income communities will depend upon the availability and accessibility of adequate job opportunities, including entry-level jobs for those residents who need to comply with work requirements to live in the mixed-income communities. Such jobs, in turn, depend upon another key indicator of economic health — the existence of commercial and retail options. Such commerce will help satisfy the unmet demand of current community residents, while attracting new residents — especially market-rate buyers and renters. Furthermore, these amenities provide opportunity for social interaction and community-building.

The Chicago Department of Planning and Development (DPD) is promoting economic development near new mixed-income housing sites, including:

- West End, the former Rockwell Gardens site;

- The intersection of 39th and State streets, which will serve both Park Boulevard and Legends South, the former Stateway Gardens and Robert Taylor Homes, respectively;

- The Cottage Grove Corridor — from Pershing Road to 51st Street — which will serve Oakwood Shores, formerly known as the Madden/Wells/Darrow site, as well as the mixed-income communities on the lakefront, Jazz on the Boulevard and Lake Park Crescent.

DPD recently announced the acquisition of a 12,600 square-foot parcel at Madison Street and Western Avenue, the last piece of a three-acre development near the Westhaven mixed-income community. A retail center with a grocery store will be built on this site.

The Partnership for New Communities, a grantmaking entity that has been created to support the success of the CHA Plan for Transformation, is currently funding different organizations engaged in economic revitalization initiatives surrounding mixed-income communities. They include:

- Metro Chicago Information Center (MCIC), which is developing baseline market, quality of life, and socioeconomic indicators in order to track change in several communities and to communicate market-relevant information to action-oriented business and community development organizations.7

- The Local Initiatives Support Corp. (LISC), which is developing and implementing Centers for Working Families in Chicago’s Near West Side and Mid-South communities. The Centers will help residents build household financial strength, access jobs and career development, and manage their finances.8

- Chicago Community Ventures, for launching the Small Business Development Initiative, providing qualified businesses located in selected Near West Side and Mid-South communities with long-term advisory services and access to capital.9

- MPC’s Employer-Assisted Housing initiative, which aims to attract affordable and market-rate residents to CHA transformation communities by providing employers located near the Plan for Transformation sites and their employees with access to housing incentives and support.10

- The Financial Research Advisory Council (FRAC), a Chicago-based nonprofit consulting organization, which has partnered with the Boston Consulting Group to evaluate potential retail investment models in these areas.

The FRAC team identified three sites in the Mid-South area and two sites in the area surrounding the new West End and Westhaven developments. According to FRAC, closing these deals will require a committed partnership between the City of Chicago, private sector, and local communities, as follows:

- The city can play a central role in removing barriers to development, by aligning resources and expediting the process.

- The private sector can support the development of appropriate partnerships and structures to make these sites viable investment opportunities and develop site and economic plans supportive of large and small business success.

- The local communities can work with local leadership and potential developers to ensure that retail development aligns with the community vision, local businesses are linked with funding and advisory resources, and key stakeholders champion support of the investments.

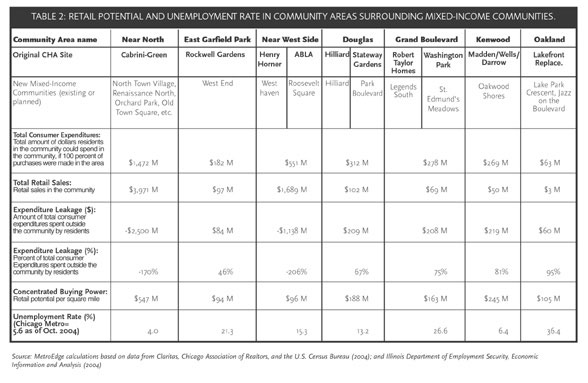

Much of the new mixed-income housing is being developed in communities that struggle with a scarcity of jobs and high unemployment rates (see Table 2). To succeed, what’s needed are:

- Linkages to jobs located within the communities and elsewhere.

- Workforce and career development options for all residents, including training, counseling and educational opportunities, with an emphasis on residents who need to fulfill work-related requirements in order to live in the community.

- An environment that is career development-friendly, including employer-assisted housing programs, quality Internet access at home, in community centers and other surrounding facilities, and childcare centers available to all residents.

With respect to commercial development, both the Mid-South area and the Near West Side show promising signs in terms of demographics, public and private investment (existing and planned), and current retail profile. Table 2 provides some economic indicators related to retail potential in a number of community areas where mixed-income developments are in place or under construction. Most of these areas show large “leakages” of expenditures, with residents having to shop, dine, and obtain other services out of their neighborhoods due to lack of retail opportunities.11 These numbers illustrate the current demand for retail and commercial activity. With the development of new housing, this demand is likely to grow.

COMMUNITY SPACE: PARKS, COMMUNITY CENTERS, AND RECREATIONAL FACILITIES

Open space, community centers, and recreational facilities located in the new mixed-income neighborhoods contribute to the success of these communities by fostering social interaction and opportunities for community building. Careful and adequate planning, design, management, and programming are needed in order to create places that offer attractive alternatives for all residents.

The Chicago Park District and CHA have a long history of cooperation that dates back to the 1940s, when both agencies began working together to provide open space and community centers surrounding the new public housing properties being developed throughout the city. More than 50 years later, the CHA Plan for Transformation has made the cooperation between the agencies stronger than ever.

One example is Fosco Park, a 57,000-square-foot community center located in the Roosevelt Square community (the former site of the ABLA homes), which will include an indoor swimming pool, gymnasium, and new daycare facility. Also, a $1.6 million campus-park has been proposed to be developed in partnership with the Park District and CPS at Grant School, which will be located at the heart of the West End community (formerly known as Rockwell Gardens). The underutilized school might be used for services such as daycare. Also, several parks recently have been renovated and reopened in the proximity of Park Boulevard (Stateway Park) and Oakwood Shores (Mandrake Park).

Other partnerships have been equally fruitful. In the Legends South area (the former Robert Taylor Homes site), the Ray and Joan Kroc Center, co-sponsored by the Salvation Army, is slated to be built on State Street between 47th and 50th streets, and will provide a solid community anchor. The proposed 28-acre, $140 million community center is scheduled to open by 2007 and will spur the creation of 250 estimated new jobs.

A recent study of community facilities around mixed-income sites in Chicago, conducted by the Illinois Facilities Fund (IFF), found that:

- There are a variety of different approaches to planning for facilities in those nine sites.

- Good demographic projections do not exist for the age breakdown of residents (IFF had to develop its own methodology).

- Services are not needed everywhere; some places are already well-served.

- Limited land and building options, as well as insufficient funding, are large barriers in some areas.

Help is needed, according to IFF, to increase the awareness of existing assets and services in these communities, establish more partnerships between existing providers, coordinate between entities that own land or buildings (such as the City of Chicago, Chicago Public Schools, or CHA), and obtain more financial support for the development of facilities where there has been a determination of need.

Some of the challenges in creating these parks and community facilities are:

- Successfully engaging current and future residents in the planning process;

- Creating well-constructed, multi-purpose facilities with high-quality programs and community assets that appeal to a broad range of income groups, avoiding situations where one sector of the community feels alienated from the use of the facilities; and

- Guaranteeing high security and safety standards in these spaces.

CONCLUSION

Local and national research on the revitalization of public housing into mixed-income communities is still a work in progress. On one hand, there is definite evidence of success, as measured by the community stability and economic prosperity of residents and neighbors. On the other hand, numerous challenges have been identified, many of them on how to develop a network of amenities and services in and around these communities.12 This report has pointed out some of these achievements and challenges in Chicago.

Since the onset of the Plan for Transformation in 1999, the CHA has worked in partnership with city agencies, nonprofit organizations, and private firms to promote the success of the mixed-income communities being developed on former CHA sites. Initial successes have happened in mixed-income communities located in economically viable areas, such as those on and near the former Cabrini-Green site. Other mixed-income communities, such as Lake Parc Place in the Oakland community and Westhaven in the Near West Side, have achieved stability in less-developed neighborhoods.

In order to make mixed-income communities succeed, partners and stakeholders need to develop “intentional and deliberate” community-building strategies on-site — as suggested by national expert Paul Brophy13 — and also implement comprehensive investment strategies in the surrounding neighborhoods. Expert Dr. Norman Johnson, involved in the redevelopment of the Centennial Place mixed-income community in Atlanta, has noted that every initiative developed to support a revitalized public housing community (whether a school, community center, park, or commercial strip) needs a champion or “angel” in order to succeed.14 Successful champions are usually committed, passionate stakeholders with a vision, able to inject energy from the very beginning, and willing to follow through the different stages of the initiative until its completion.

In the words of Jeremy Nowak, president and CEO of The Reinvestment Fund of Philadelphia, positive, sustainable economic change in redeveloping communities will most likely occur step by step, “from the particular to the general, rather than through ‘sweeping’ reforms in the absence of tangible practice.”15 According to Lawrence Vale, head of the Department of Urban Studies and Planning at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, a critical piece in the process of creating a successful community is to foster “that intangible sense of ownership”16 among residents that makes everybody feel part of a common enterprise.

While evidence shows that initial local successes have occurred,17 the challenges of creating healthy communities (both within and around mixed-income developments) will be greater in areas that need to attract a significant amount of market-rate renters and homebuyers, and where there has been long-term disinvestment. Any and all angels and champions are encouraged to apply.

ENDNOTES

- See the article “Chicago and Atlanta share lessons learned on education and quality schools” at www.metroplanning.org/article Detail.asp?objectID=2033.

- See the article “Commercial development and job opportunities, key elements for the success of the mixed-income communities created by the CHA Plan for Transformation” at www.metroplanning.org/articleDetail.asp?objectID=2212

- See the article “Public forum explores the role of parks and community centers in the creation of healthy mixed-income communities” at www.metroplanning.org/ourwork/articleDetail.asp?objectID=2310.

- Bounded by 31st and 47th streets, from the Dan Ryan expressway to Lake Michigan (Bronzeville-Grand Boulevard area).

- For details on the unit breakdown and development status at these communities, see MPC’s July 2004 CHA Plan for Transformation Progress Report, available at https://metroplanning.org/article Detail.asp?objectID=2237.

- More information is available at www.ren2010.cps.k12.il.us.

- More information is available at www.mcic.org.

- More information is available at www.lisc.org.

- More information is available at www.chiventures.org.

- More information is available at www.metroplanning.org/articleDetail.asp?objectID=2250.

- The main exceptions are the Near North area, which includes the affluent Lincoln Park/Gold Coast neighborhoods, and the Near West Side, one of the largest community areas in the city covering 3,200 acres. As the table shows, these two community areas attract a significant amount of customers from other parts of the city.

- A number of recent studies are available on the early achievements and challenges associated with the redevelopment of public housing as mixed-income communities. See, among them, the U.S. General Accounting Office report “Public Housing: HOPE VI Residents Issues and Changes in Neighborhoods Surrounding Grant Sites” of 2003; the recent study by Sudhir Venkatesh and Isil Celimli “Chicago Public Housing Transformation: A Research Report,” published by the Center for Urban Research & Policy of Columbia University; the series by Susan Popkin et al. “A Decade of HOPE VI: Research Findings and Policy Challenges,” published by the Urban Institute in 2004; or the forthcoming study by Mindy Turbov and Valerie Piper “HOPE VI as a Catalyst for Neighborhood Change,” to be released by The Brookings Institution.

- See the article “The Future of Public Housing: A National Perspective on Creating Successful Mixed-Income Communities” available at www.metroplanning.org/articleDetail.asp?objectID=1906.

- See endnote 1.

- See endnote 2.

- See endnote 3.

- See U.S. General Accounting Office (2003) “Public Housing: HOPE VI Residents Issues and Changes in Neighborhoods Surrounding Grant Sites”; and James Rosenbaum et al. (1998) “Lake Parc Place: A Study of Mixed-Income Housing”, published by Fannie Mae Foundation.