Our Equitable Future

A Roadmap for the Chicago Region

The work we can all do to uproot our legacy of segregation and accelerate change.

A path forward

Chicago’s segregation is inextricably linked to racism. To break this cycle, our path forward must be rooted in racial equity. Doing so will unlock the potential of all the region’s residents and communities.

In 2015, the Metropolitan Planning Council launched a groundbreaking study to calculate the economic costs of segregation. With the Urban Institute, we documented the extreme price we pay to live so separately by race and income. Our study revealed this singular truth: As residents of the Chicago region, our fate is shared, and by living so separately we pay a steep cost that can be measured in lost income, lost lives and lost potential. These findings have been a catalyst for meaningful action, bringing together people from diverse communities and sectors to develop solutions that will lead to a more and equitable and thriving Chicago region.

Together with more than 100 advisors and issue-specific working groups, we identified 25 needed policies and interventions that better equip everyone living in our region to participate in creating a stronger future. We have built our case for the benefits of a more equitable Chicago region.

The work ahead is urgent and hard, yet doable. And in some cases, it’s already happening.

The number of government, community and business leaders who are taking action to make our region more equitable and inclusive is growing larger every day. Innovative efforts like the City of Chicago’s Neighborhood Opportunity Fund, JPMorgan Chase’s $40 million investment in disinvested neighborhoods, the Chicago Regional Growth Corporation (newly formed to catalyze inclusive regional economic growth), and Chicago United for Equity’s first-ever use of a Racial Equity Assessment in Chicago—these are just a few examples.

Our recommendations build on these programmatic innovations by pushing for deeper change; change that directly addresses entrenched racism. We cannot afford to chip away slowly at inequities, program by program. Our institutions must fundamentally change.

Prioritizing equity and inclusion can have great economic and social benefits for the entire region. MPC’s analysis of the recommendations show tangible outcomes such as:

- An extra $218 million in spending towards the regional economy if a City Earned Income Tax were adopted

- 3,377 more available housing units if CHA housing vouchers were expanded

- $198 million saved annually by eliminating unnecessary pretrial detention

Now is the time to invest in our future by investing in equity and inclusion.

Our roadmap: Recommendations for advancing equity and inclusion

In MPC’s March 2017 Cost of Segregation report, we explicitly emphasized the enormous price we pay for segregation. Yet, the remedies and recommendations offered here go far beyond the patterns of where people live. To disrupt metropolitan Chicago’s legacy of segregation, we focus on the racism and inequity that fueled and continues to fuel it. Fundamentally, segregation and its resulting inequities are by-products of racism—which is why the solutions in this report focus on racial equity and inclusion as the root goal.

Attaining a more equitable and inclusive region can only occur when two paths are simultaneously and rigorously pursued.

Roadmap to Equity Part 1

Dismantle the institutional barriers that create disparities and inequities by race and income

This is known as a racial equity framework and it is a practice that EVERYONE can adopt: government, private sector, philanthropy, community organizations and individuals.

Roadmap to Equity Part 2

Pursue policies and programs that can be implemented right now

The following recommendations are comprehensive but not exhaustive. There are many more good ideas and implementers; these are a sampling that we believe get us off to a strong start.

In addition, there are a few key areas that are not yet included in this roadmap. In the Under Study section, we identify topics like a progressive tax structure and determining the right supports for small businesses that call out for further study and serious consideration.

What we have set forth are actions we can take today.

Oak Park adopts racial equity

Oak Park Mayor Anan Abu-Taleb and Village Trustee Bob Tucker are leading efforts to advance racial equity.

Oak Park is known for being a progressive and inclusive community, and the reputation is well-deserved.

From the historic Fair Housing Ordinance of 1968 to the recent Welcoming Village Ordinance which established Oak Park as a sanctuary city, the Village has a long history of addressing racial diversity and inclusiveness. But it’s challenging itself to do more.

“One of the big issues for those of us who serve on the Village Board is that we don’t know what we don’t know,” says Bob Tucker, Village of Oak Park Trustee. “We need to be mindful of the people we serve and better take into consideration how our decisions impact all the people in our community.”

That’s why Oak Park is taking steps towards adopting a racial equity framework, which, for them, means implementing training, tools and resources that dismantle the institutional barriers that create disparities by race and income. And they aren’t the only ones in their Village. Other entities, like the schools, park district and library are also adopting this approach.

“We all have a role to play in addressing racial equity,” says Anan Abu-Taleb, Mayor of Oak Park. Mayor Abu-Taleb immigrated to Chicago from the Gaza Strip and raised his family and built his business in the Village. “I made Oak Park my home because I feel welcomed here and have a strong sense of belonging. As Mayor, I have a role to play to ensure the people I serve feel like they belong here too, that they have a voice and can meaningfully contribute. It’s the only way we will all win.”

Advancing racial equity

“Policies have been enacted for years and years which have created gaps in equity. The residual impact manifested from those policies is what we currently are witnessing. There should be two things happening to rectify the situation- get rid of the barriers that produce racial inequality and empower people to be able to do their best. Some of our current policies are just band aids.”

—LaShone Kelly, Housing Counselor, Garfield Park Community Council

Roadmap to Equity Part 1:

Dismantle the institutional barriers that create disparities and inequities by race and income

Geography: Chicago Region

Issue

The cost our entire region pays for its segregation is steep, measured in lost income, lives and education. While black and brown communities are disproportionately harmed by lack of opportunity, exclusionary development and unjust policies, we all pay a price for this separation. And simply put, it’s a cost we cannot afford.

At the heart of our recommendations is a guiding principle: the only way our region and its residents will reach their full potential is by dismantling the barriers that create disparities and inequities by race and income. It is essential for our growth and our shared prosperity.

Many examples of local progress are highlighted in this roadmap. As a city and region, we should be proud of the programs we have put in place that acknowledge and address our inequities. We also know, however, that governments, businesses and organizations that are most effectively addressing inequities are marrying this programmatic approach with an institutional change approach. This larger commitment moves beyond programs to rigorously examine structures, such as budgets, hiring practices, plans and ordinances that may be perpetuating inequities, regardless of intent.

This is what’s known as a racial equity framework.

Recommendation

Institutions and individuals across all sectors implement a racial equity framework.

All of us have a role to play:

- Government: The government sector has a constitutional obligation—and statutory powers—to end the segregation of people, power and resources, and demand it of others as well. This means a commitment to not only creating new mechanisms to address disparities, but to changing the institutional systems that perpetuate them through ongoing staff training, equity assessments of any proposed initiatives and investments, and public accountability to progress on goals.

- Private sector: Moving beyond traditional corporate diversity and inclusion efforts to assessing and promoting equity in every aspect of business operations, including playing an active role in addressing Chicago’s violence. This could include investing in a diverse, job-ready workforce, creating opportunities for training and advancement, providing fair and reliable schedules and benefits that reduce the racial wealth gap such as a living wage, health care and retirement benefits.

- Philanthropy: Committing to examine how grantmaking—with an explicit equity lens—can improve outcomes. For instance, in 2017 the Field Foundation of Illinois shifted to grantmaking with equity as a core value. Embedded in this change is an emphasis on funding with a racial equity lens by allocating 60 percent of grant dollars to organizations by, for, and about serving ALAANA (African, Latino, Asian, Arab and Native American) individuals and communities throughout the Chicago area.

- Civic and Community Organizations: Both ensuring that not only external programming addresses inequities and turning the equity lens inward to examine and reconfigure hiring, promotions, board composition and decision-making structures.

- Individuals: Understanding and counteracting on our own internal biases as well as better recognizing of the structures of oppression in which we all operate. Some areas of self-reflection and work needed may include biases about race, sexual orientation, gender, age and level of ability. Further, we have an individual responsibility to make decisions that break down, rather than add to, our region’s patterns of segregation and disinvestment, such as where we live, what businesses we support and where we send our children to school.

These institutions and individuals have worked together to create oppressive systems. They—and we—will have to work together to dismantle them.

How it would work

Steps to a racial equity framework for institutional change include:

- Build knowledge and capacity agency by agency, department by department: All staff—from teachers to police officers to judges to medical personnel—receive implicit bias and individual/systemic racism awareness training and it is also a required component of new staff orientation. Staff self-select to be part of each agency’s or department’s “Change Team.” These groups receive initial and ongoing training, and lead in-department use of racial equity assessment tools. Attention is paid to Change Teams reflecting a range of positions, race, gender, etc. to ensure the work is embraced throughout the organization.

- Use racial equity assessment in decision making: Tools are employed immediately to analyze disparate impacts by race and plan accordingly on the front end, such as in proposed budgets, ordinances or other policy changes and in practices such as hiring and contracting. Measurable indicators of success/impact over time are created for accountability.

The Racial Equity Tool[1] is a simple set of questions:

- Proposal: What is the policy, program, practice or budget decision under consideration? What are the desired results and outcomes?

- Data: What does the data tell us about the problem or the solution? When we disaggregate data by race and income, what does that tell us?

- Community engagement: How have communities—especially those most impacted—been engaged? Are there opportunities to expand engagement?

- Analysis and strategies: Who will benefit from or be burdened by the proposal? What are the strategies for advancing racial equity or mitigating unintended consequences?

- Implementation: What is the plan for implementation?

- Accountability and communication: What is the plan to ensure accountability, communicate and evaluate results, especially to and for those most impacted?

Where this is working: Elevated Chicago

Elevated Chicago is a collaborative of nonprofit, governmental and business organizations, created to promote racial equity through public health, arts and culture and climate change resiliency in Chicago’s neighborhoods. By focusing on equitable transit-oriented development, Elevated Chicago is improving neighborhoods—without displacing current residents—by attracting and aligning capital, supporting community-driven interventions, changing policies and narratives, and sharing knowledge.

Here’s how Elevated Chicago has embodied racial equity in its approach and practices:

- Its 16-member steering committee, working groups and community-based tables all include people of color in leadership positions and representation of organizations based in majority-African-American and majority-Latino communities.

- All Steering Committee members and their proxies have received racial equity training and an individual and collective assessment of their cultural competency followed by one-on-one coaching.

- All participating organizations have made a commitment to values and rules of engagement that promote diversity, inclusion and equity in meetings, decision-making and learning opportunities, and meeting agendas include explicit rules of engagement. Co-chairs have been appointed to ensure they are used.

- All capital investments and programmatic grants are designed to benefit primarily the communities where Elevated Chicago works (all of which are majority-African-American or majority-Latino). Applicants must demonstrate meaningful community engagement in all funding proposals.

- Elevated Chicago has also made a commitment to compensate organizations that increase diversity and racial equity within the collaborative. A pool of funds has been set aside to make flexible grants to community-based organizations led by and/or serving people of color. The dollars can be used as stipends to pay for the time devoted to Elevated Chicago work by leaders and staff of these organizations, and for associated costs (such as travel, parking, meals, daycare costs, etc.) and to ensure that the voice and power of community residents of color is represented authentically, inclusively and effectively.

Elevated Chicago acknowledges that, like many other organizations and collaboratives, it is on a journey to become more diverse, inclusive and equitable and that there is much more to do to ensure full diversity, inclusion and equity in its work.

Roadmap to Equity Part 2:

Pursue policies and programs that can be implemented right now

Elevated Chicago promotes inclusive development near transit stations

Elevated Chicago partners Juan Carlos Linares and Joanna Trotter outside the Logan Square Blue Line Station, one of the collaborative’s focus areas.

Chicago is at a crossroads: Rapid development and gentrification pressures some communities, in many cases near transit stations.

Alongside new investment, rising prices displace residents and small businesses. While we are at a crossroads, this is also a moment of opportunity. We can leverage development for the benefit of longtime residents and the preservation of unique local culture.

One technique is transit-oriented development. That’s the work of Elevated Chicago, a partnership of organizations committed to transforming the half-mile radius around transit stations into hubs of opportunity and connection across our region’s vast transit system.

Elevated Chicago uses the spaces around transit stations as the tool through which to tackle our region’s biggest issues: segregation, inequity, displacement and gentrification.

“As we look along one of our region’s greatest assets, our transit lines, we see stark disparities. [Elevated Chicago] is one way to tackle them,” says Joanna Trotter, Senior Program Officer of Economic and Community Development for The Chicago Community Trust. “The people being displaced are the ones who need [transit] the most.”

“Transit, particularly like the Logan Square Stop, should always be an inclusive amenity,” said Juan Carlos Linares, Executive Director of the Latin United Community Housing Association (LUCHA), a nonprofit on Chicago’s northwest side that works in affordable housing development and housing counseling.

Trotter and Linares participate in Elevated Chicago, whose unique power-sharing structure gives community residents and people of color the same power and influence as funders and heads of city departments.

While growing the power-sharing model is important work, Trotter recognizes that more efforts like Elevated Chicago are essential. “As a system, there are inequities that have lasted for decades,” Trotter says. “We’ve still got work to do in Chicagoland.”

1. Targeting economic development and inclusive growth

Inclusive growth is a process that encourages long-run growth by improving the productivity of individuals and firms in order to raise local living standards (prosperity) for all (inclusion).[2]

The Chicago region needs an inclusive growth strategy to maximize the ability of all people and places in the region to contribute to and benefit from the economy. Building a more inclusive economy will produce benefits for everyone by tackling the racial and economic inequities that are currently undermining our ability to grow. Putting the region on a higher growth and prosperity trajectory cannot be accomplished by any single solution. Rather, it requires a sustained commitment to systems change across a multi-sector group of organizations and leaders committed to making our economy work for everyone, including through redirecting existing funds to more inclusive uses. The impacts of this important shift aren’t likely to be seen immediately, but are nonetheless essential to unlocking new, wealth-producing economic opportunities for low-income and communities of color, and—by extension—helping the region overall prosper.

Neighborhood Opportunity Fund Entrepreneur Skyler Dees

Neighborhood Opportunity Fund entrepreneur Skyler Dees in his new storefront space.

Skyler Dees began cooking when he was two years old. It’s a passion that drove the 27 year-old North Lawndale native to become a self-taught chef. “As I thought about entering the workforce, I realized that I could cook,” he says. “And more important, it fulfilled me.”

Dees wanted to start his own catering business. But, like many entrepreneurs of color in Chicago, he soon realized he was up against numerous social and economic challenges. It was a reality that made his dream seem almost impossible.

“The personal equity that I had in my company could only get me so far,” Dees says.

With the help of Alderman Michael Scott of the 24th Ward, Dees acquired a storefront space at the MLK Legacy Apartments. The building, which is just steps away from where Dees grew up, is located right along a stretch of 16th Street that offers few healthy and fresh food options. A GoFundMe campaign was the first step in launching his business. And even though he secured more than $2,000 in donations, it wasn’t nearly close to what he needed.

That changed in May 2017 when he won the inaugural City of Chicago Neighborhood Opportunity Fund, a grant that Dees used to help build out a commercial kitchen. It’ll take $75,000 for Dees to complete the buildout, including the installation of professional cooking and refrigeration equipment. The Neighborhood Opportunity Fund grant is paying approximately 65 percent of the total cost.

“It definitely helped me bridge the gap between what I was doing with my company and what I had the potential to achieve,” he says.

Launched in 2016 by Mayor Rahm Emanuel, the Neighborhood Opportunity Fund generates money from downtown growth to support commercial and cultural developments in communities that have experienced underinvestment for decades, primarily on the South and West Sides. Since then, it’s supported the development and expansion of more than 60 businesses and cultural assets. The additional capital has been a game changer for Dees and other awardees, but he hopes to see more investments in communities across Chicago.

“It’s allowed me to have equity in the future that Chicago is building,” Skyler says. “But there’s so much work that needs to be done.”

-

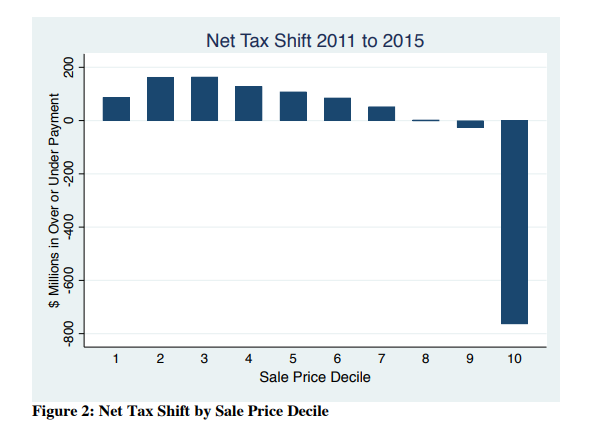

Establish a graduated real estate transfer tax

Implement a graduated city real estate transfer tax to generate additional revenue in a progressive manner.

Geography: City of Chicago

“Economic development has to be seen as human capital development, the two have to be seen in concert.”

—J. Brian Malone, Executive Director, Kenwood Oakland Community Organization (KOCO)

Issue

In typical real estate transactions within Chicago, a transfer tax is charged by the State of Illinois, Cook County and the City of Chicago. 50 percent of the real estate transfer tax (RETT) revenue collected by the State of Illinois is deposited into the Illinois Housing Trust Fund (IAHTF), which is administered by the Illinois Housing Development Authority.3 The IAHTF provides flexible gap financing for affordable rental and for-sale housing across the state.

Federal resources are critical for local and state governments who rely on these funds to provide services from housing, to transportation, education, health and other supports for residents. Historically, federal funds have comprised about one-third of state budgets.4 With these funds increasingly at risk at the federal level, our region, like many others, will need to identify other innovative proposals to meet local housing needs in an equitable manner.

Recommendation

Implement a graduated city real estate transfer tax to generate additional revenue in a progressive manner.

How it would work

Currently, the City imposes a RETT of $5.25 per $500 of property sale value ($3.75 goes to the City and $1.50 to CTA). According to analysis by the Center for Tax and Budget Accountability, under a graduated rate structure as proposed below, nearly 95 percent of property transactions citywide would receive a tax cut on the sale of properties.

Taxable value Rate structure <$500,000 0.35% $500,000–$1m 1% $1m–$5m 2.5% >$5m 3.3% Under the proposed graduated structure, the first $500,000 in value would be taxed at the 0.35 percent rate and the incremental value beyond would be taxed according to the rate structures noted above. As a home rule municipality, the City of Chicago would need referendum approval in order to make the proposed changes to the RETT structure. The proposed graduated RETT would generate an estimated $100–$185 million in additional revenue beyond the current transfer tax. The revenues would be used to pay for services such as addressing homelessness, supporting affordable homeownership through programs like New Homes for Chicago and establishing a city-based Earned Income Tax Credit.

-

Prioritize and measure economic growth that creates opportunities for everyone

Collaborate to establish a common approach to inclusive growth.

Geography: Chicago Region

“Economic development has to be seen as human capital development, the two have to be seen in concert.”

—Jawanza Brian Malone, Executive Director, Kenwood Oakland Community Organization (KOCO)

Issue

While the Chicago region seeks and tracks economic growth, we do so without explicit focus on jobs that help workers achieve both employment stability and upward mobility. Currently, any job growth may seem like a win—but if growth is mainly in low-wage jobs without stable schedules, it advances neither inclusive growth nor a healthy labor market. Another factor to consider is the distribution of job growth; while the number of jobs in the Loop, Near North Side and Near West Side increased by 65,000 from 2010 to 2015, jobs in those communities held by South and West side residents decreased. In short, we lack a coordinated goal for growing an inclusive economy that deliberately advances businesses and workers of color and the metrics to evaluate progress. Establishing inclusive growth metrics will not change segregation on its own, but it will encourage organizations and leaders across the region toward a common goal and means of measuring progress towards it.

Recommendation

Local and regional organizations, governments and leaders should collaborate to establish a common approach to inclusive growth, along with metrics to measure progress and criteria by which to evaluate future investments. These metrics will prioritize opportunities that have a real impact, including the extent to which the entire population is participating in growth and prosperity, such as through employment, particularly among key segments of the population by race and ethnicity.

How it would work

The Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning (CMAP), World Business Chicago and Local Initiatives Support Corporation would initiate the process of outlining a shared vision for inclusive growth, including defining shared goals and metrics for inclusive growth in the Chicago region.

Case study

The Minneapolis-St. Paul Regional Economic Development Partnership recently launched a Regional Indicators Dashboard,[5] a detailed set of measures that can be tracked over time to assess the strength of the regional economy in providing inclusive growth. The dashboard reflects the efforts of multiple organizations and leaders to agree on common performance outcomes and then track and share progress.

Impact

By 2020, government and civic leaders will commit to a common set of performance measures to evaluate the region’s yearly progress on jobs, education and income for people across racial and economic backgrounds. Minneapolis’ dashboard initiative has been tracking performance outcomes such as the graduation rates for white students and students of color, and the employment gap in the region between white residents and residents of color. Between 2015 and 2017, they noted a closing of the latter gap, from thirteen percentage points to ten percentage points. Adopting a similar tracking system in the Chicagoland region would 1) allow policymakers to understand which aspects of inclusive growth merit the most immediate attention and 2) illuminate efforts which are already working well and should be leveraged.

-

Invest equitably across the region

Focus investment in targeted areas with existing infrastructure assets.

Geography: Chicago Region

Issue

Disinvestment is costly and too many of our region’s communities of color—especially on the South and West Sides of Chicago and Cook County, as well as in areas in and around Waukegan, Aurora, Elgin and Joliet—have experienced long-term job and population loss, increased violence and an inability to attract businesses and other investments. In many other parts of the nation, regional reinvestment goals have created a spark for economic stabilization and growth in target areas for investment. This approach has succeeded in such diverse regions as San Francisco, Denver, Atlanta and northwest Indiana.

Recommendation

Focus investment in targeted areas with existing infrastructure assets, such as transit, to bring growth to areas that have experienced prolonged disinvestment.

How it would work

How it would work: CMAP would establish a Targeted Reinvestment Area (TRA) program as part of the ON TO 2050 plan, as currently proposed in the plan’s preliminary recommendations. MPC would work in partnership with CMAP and other advocacy organizations to ensure that the program is locally driven, involves a wide range of agencies that invest in infrastructure, and work with disinvested communities to implement investments without displacement.

Case study

The Livable Centers Initiative (LCI), managed by the Atlanta Regional Commission (ARC), has focused transportation investment into target geographies, typically transit-oriented urban and suburban downtowns. LCI funds are prioritized for areas that fall within the “high to very high” zones of ARC’s Equitable Target Areas Index.[6] Since 2000, $172 million in transportation funding has been directed to these areas, mainly for active transportation improvements.[7] With this targeted infrastructure investment has come 77,000 new housing units since 2000, many of them multi-family, accompanied by nearly 90 million square feet of office and commercial space.[8]

Impact

Establishment of a program that directs funds to targeted communities will allow for already-existing assets in disinvested areas to be leveraged and expanded. As noted in ON TO 2050’s preliminary land-use recommendations, “focusing resources in areas that are a local priority can make the best use of constrained funding. By strategically targeting investments toward community main streets and regional economic centers where infrastructure already exists, we can maximize the impact both of those new expenditures and of the earlier ones when such areas were originally developed.”

-

Make vacant lands an asset

Build capacity among community-based organizations and suburban municipalities to redevelop vacant land.

Geography: Cook county and one South and one West side community near a CTA transit station

“There’s a ton of vacant land, but there hasn’t always been much of a vision or thought of what may come after it. ‘Let’s just tear it down because the building is an eye sore’…There hasn’t been a lot of follow through with what can happen with our vacant land.”

—Pete Saunders, Calumet City Economic Development Coordinator

Issue

After a century of deliberate disinvestment through redlining, contract selling and predatory loans, coupled with more recent deindustrialization, many communities on the West and South sides of the City and Cook County have a concentrated inventory of vacant, foreclosed and tax-delinquent properties.[9] The Cook County Land Bank alone has over 18,000 properties in their pipeline, including residential, industrial, commercial, and vacant lots. Vacancies have a profound negative impact on communities, including a higher incidence of criminal activity and higher levels of stress and anxiety among residents.[10] If harnessed strategically, however, vacant land and property can also be an asset and an opportunity to proactively redesign a community’s participation in the regional economy.

Recommendation

Recommendation: Build capacity among community-based organizations and suburban municipalities to enter into targeted land banking agreements with Cook County Land Bank Authority (CCLBA) and South Suburban Land Bank and Development Authority (SSLBDA) to redevelop vacant land. Particularly in the South Suburbs, create new types of development entities with the forms, capacities and powers to impact a wide range of development sectors (e.g., real estate, workforce development, supply chain and cluster growth, etc.).[11]

How it would work

CCLBA and SSLBDA have the ability to enter into land banking agreements with community organizations and municipalities. Under this agreement, communities determine a strategy and plan for the vacant land and work with the land bank to have them hold or “bank” vacant land or properties within a given geography for an agreed upon time period. Communities would take the lead in setting the vision for the land, but would be provided technical assistance around developing a strategy, building capacity around a community-ownership model, if desired, and identifing funding and capital sources. Vacant land could be transformed into community facilities, open space, retail development or housing.

Case study

Chicago Neighborhood Initiatives (CNI), in efforts to increase homeownership in the Pullman neighborhood, acquires and rehabs vacant properties. This process, however, can present challenges—such as finding owners of abandoned properties, acquiring properties clear from taxes and other encumbrances. To help with these efforts, CNI partnered with the Cook County Land Bank Authority (CCLBA) to enter into a community land banking agreement. CCLBA acquires and maintains properties on behalf of CNI and, for a nominal fee per property, holds them until CNI is prepared to apply for Low Income Housing Tax Credits to rehab the properties. Through this partnership, CNI can leverage the authority and powers of the CCLBA to ultimately take ownership of these properties, drive community investment and build stable homeownership in the Pullman neighborhood.

Impact

Putting vacant land and properties to productive use saves municipalities money they would otherwise pay for upkeep and maintenance, provides increased tax revenue and public safety and mental health benefits for community residents. If vacant land is successfully converted to a jobs-generating use, the local and regional economy benefits as well. Community ownership models, such as land trusts, provide opportunities to build sustainable, affordable homeownership and equips community stakeholders to guide decision-making around future development. Assuming conversion of 50 vacant Land Bank parcels across one South Side and one West Side neighborhood—resulting in 25 residential developments in each—we estimate property tax generation of approximately $153,300 per year in the aggregate.

-

Improve health through publicly funded development

Any government entity issuing public requests for proposals requires developers bidding on the RFP to detail how the proposed development will positively impact health in the surrounding community.

Geography: Region

Issue

For many residents of low-income communities of color, continual disinvestment has resulted not only in reduced incomes and educational attainment, but also in poor health outcomes. Due to inequitable distribution of resources, low-income areas and communities of color are more likely to lack resources that promote health, such as affordable high-quality housing, green space, retail options (grocery stores and other) and gyms.[12] As such, those who live in in low-income and communities of color have worse health outcomes than those in areas that are affluent and white: In Chicago, for example, people living in Washington Park will die 14 years earlier, on average, than those in adjacent, more affluent Hyde Park.[13] Traditionally, development in disinvested areas has attempted to solve for rent burden or employment needs, but rarely for health deficits. Many tools exist for assessing the health of a community and determining how the built environment can improve individual or community health, such as Enterprise Community Partners’ Opportunity 360[14] and the WELL Building Standard guide.[15] Explicitly making health criteria part of evaluation for development with public land and/or public money can encourage development that not only does not add to health disparities but proactively prioritizes health.

Recommendation

Any proposal seeking government-owned land or government money must detail the range of ways the proposed development will impact health in the surrounding community.

How it would work

Taking the example of a department issuing a Request for Proposal (RFP), the RFP/RFQ packet would include health information for every publicly funded project, and require developers to state the positive and negative effects the proposed development will have on the health of the surrounding neighborhood. The issuing department will consider health impacts among the deciding criteria. Health considerations can be as direct as an industrial user committing to use electric trucks to reduce emissions and respiratory risk, or as broad as including a large amount of affordable housing to help prevent displacement. In Chicago, this strategy aligns with and moves forward the Health in All Policies Task Force recommendation of including health criteria in public RFPs,[16] and the Chicago Department of Public Health could provide health impact data customized for each RFP.

Case study

The Cook County Land Bank recently partnered with the Metropolitan Planning Council and the Chicago Department of Public Health to conduct a participatory planning process for the redevelopment of a vacant Woodlawn building. The process included sharing health data with residents and eliciting which health values and needs could be addressed and improved by development features of the building. CDPH and MPC then analyzed residents’ scenarios to determine the health benefits of each. Ultimately, CCLB will use recommendations from this process to build an RFP that reflects the priorities of the community.

Impact

Ultimately, including health in development can improve health outcomes. For example, if truly affordable housing is developed with adequate safety and lighting in a walkable neighborhood, that could lead to significant prevention of or decrease in Type II diabetes rates among residents who begin walking regularly, ultimately saving an average of $7,900 per person per year on medical costs.[17]

-

Use equity as a key measure for transportation planning efforts

Adopt equity as a performance measure in planning and evaluating transportation services and investments.

Geography: Chicago region

Issue

Cities and regions often use equity as a standard when making decisions about housing, economic development and other aspects of our built environment. However, when making transportation decisions in greater Chicago, historically there has been little consideration of equity in project development and prioritization. Safety, delay reduction and ridership are often prioritized, and as a result, transportation investments are likely to be made in areas of affluence with established economic activity. Smart, targeted and equitable transportation investments can generate enormous benefits such as increased access to jobs and healthier, more sustainable communities.

Recommendation

Adopt equity as a performance measure in planning and evaluating transportation services and investments.

How it would work

MPC will work with public agencies that prioritize transportation investments to recommend ways to incorporate equity-oriented project prioritization criteria and evaluate their effectiveness. CMAP is laying the groundwork for such considerations through its identification of Economically Disconnected Areas and proposed use of some equity-oriented criteria in the ON TO 2050 long-range plan. Councils of Mayors receiving federal Surface Transportation Program (STP) funds can select from six ON TO 2050 criteria as part of their project programming process, one of which is equity oriented. Additionally, the Councils of Mayors and the City of Chicago have established a new shared fund that is meant to pay for larger, transformative projects that individual STP allotments would not be able to cover. CMAP and the Councils of Mayors are in the process of developing prioritization criteria for this new allotment, which can be informed by this research. MPC will review best practices from other regions for incorporation of equity into transportation project prioritization that can be adopted in the region, and MPC will potentially develop new options. Additionally, as new methods of prioritizing projects including equity-oriented criteria are implemented, it will be important to conduct regular evaluations of the results of these new processes and make ongoing refinements to achieve desired outcomes. Therefore, MPC will also review best practices for conducting equity-oriented evaluation of planned projects and recommend a framework for future evaluations.

Case study

For Plan Bay Area 2040, the Metropolitan Transportation Commission conducted a geographic and socioeconomic equity analysis of transportation conditions. The analysis considered whether and how certain transportation conditions disproportionately affect certain areas of the city and/or disadvantaged communities. The analysis provides insight into the types of metrics that should be considered in developing equity-oriented criteria and how their outcomes can be evaluated.

Impact

Explicit consideration of equity in planning for transportation investments is expected to result in a better transportation access and outcomes for residents of communities with low-income and non-white populations, who generally have longer commutes. Evaluation of application of new equity criteria will determine whether their use is resulting in increased equity in transportation outcomes throughout the Chicago region.

-

Help local governments build capacity needed to thrive

Develop tailored initiatives to increase municipal capacity, equipping smaller and lower-income communities to more effectively address their unique challenges.

Geography: Chicago region

Issue

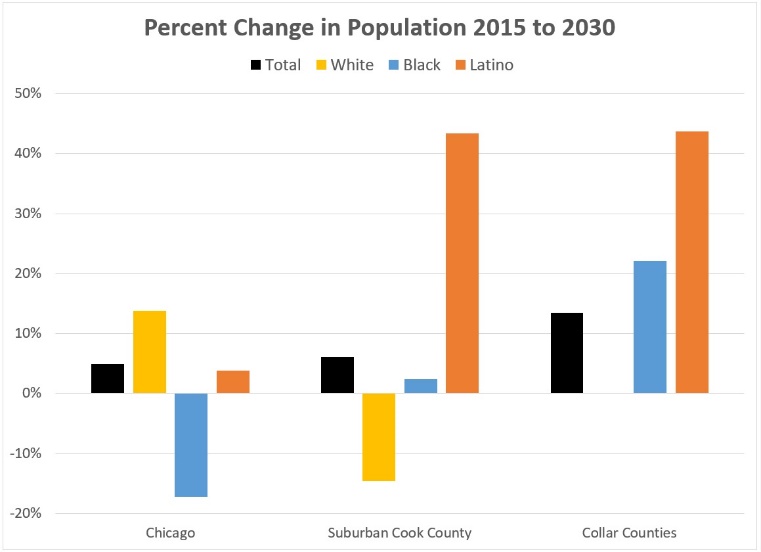

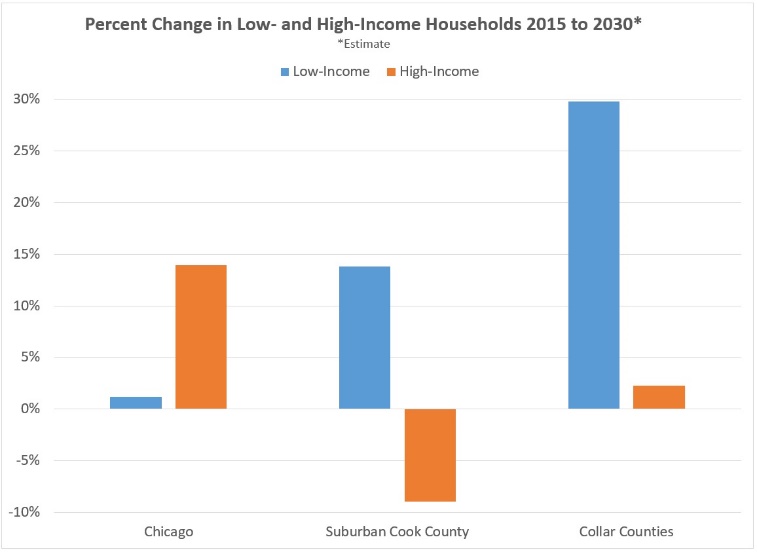

A decade ago, 60 percent of our region’s poverty was in the city of Chicago. Today, it’s less than half. But in the suburbs and nearby cities, poverty is on the rise. Our projections show this shift to rising poverty outside the city of Chicago will continue at least through 2030. This demographic change places new and difficult responsibilities on suburban communities, particularly in areas like south Cook County where poverty rates have risen most significantly.

The Chicago region contains 283 municipalities outside Chicago, including more than 130 in Cook County alone. Many smaller, low-income municipalities have found the need for constituent services rising at the same time that deindustrialization has depleted their tax base. The result: High property tax rates in places that are already struggling to attract economic development. Many municipalities are forced by their fiscal situations to defer infrastructure maintenance, cut back on basic services and limit proactive planning for the future. At the same time, they lack the staff capacity to apply for and manage grants that could help them solve their problems, let alone investigate cost-saving service sharing arrangements with their neighbors.

Recommendation

Develop tailored initiatives to increase municipal capacity, equipping smaller and lower-income communities to address their unique challenges. Likely assistance includes legal advice on service-sharing agreements, training programs for municipal decision-makers, networking programs for municipal staff, review and analysis of development proposals and many others.

How it would work

To address this range of issues, in fall 2017, MPC and the Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning (CMAP) released a strategy paper on municipal capacity.[18] MPC will coordinate with CMAP and other groups such as the Metropolitan Mayors Caucus to design a program to build municipal capacity, seek startup and sustainable funding to support it and launch a program by the end of 2018.

Impact

Many small, predominantly low-income suburban communities in Cook County have been able to proactively plan for their futures as a result of CMAP’s Local Technical Assistance (LTA) program. As of December 2017, CMAP has worked across the region to complete 135 projects, including comprehensive plans, zoning ordinances and similar products for lower-income communities including Chicago Heights, North Chicago, Park Forest, Richton Park and many others.

CIBC helps entrepreneurs launch businesses

Dr. Latasha Taylor and her mother, Marilyn Sturden, opened Flammin in the Chatham neighborhood with the help of CIBC’s Shantel Hampton (center).

As an assistant principal of a Chicago vocational school, Dr. Latasha Taylor interacts daily with young people eager for jobs. These days, Taylor offers jobs directly—thanks to Flammin, a restaurant she opened in Chicago’s Chatham neighborhood in October 2017 with her mother, Marilyn Sturden.

“I have employed six part-time workers from the Chicago Public Schools system. I also employ…recent graduates who live in this area code, 60619,” Taylor says. “Some of them don’t have families, so we are like their extended family. It gives them hope to be an entrepreneur one day themselves.”

Taylor and Sturden opened Flammin with the help of CIBC Bank USA, formerly The PrivateBank, which was acquired by CIBC in 2017. CIBC continued The PrivateBank’s commitment to investing in communities through loan products for people who might otherwise have trouble accessing capital, people like Marilyn and Latasha. Flammin’s famous Kool-Aid and fried mustard catfi sh, the beautiful interior and glistening kitchen equipment, were all made possible thanks in part to CIBC’s investments in Chicagoland entrepreneurs.

Shantel Hampton is a Relationship Manager in community small business lending with CIBC. As a child of an entrepreneur, Hampton says that her work with CIBC improves people’s lives, which strengthens the fabric of society.

“Small businesses make up the majority of all businesses in America,” Hampton says. “If we can give owners the… capital they need to start and grow, we’re going to give jobs to people. We’re going to help people own their homes and go to school. It’ll change the economic structure of an entire community.”

In Chatham, that’s true for Flammin: The restaurant offers employment, a safe gathering space and a vibrant storefront that anchors the restaurant’s small stretch of 75th Street. And of course, mouth-watering ribs.

Aon’s apprentice program with Chicago’s City Colleges

Juan Salgado and Bridget Gainer launched an apprentice program at Aon, employing hundreds of Chicago youth.

Chicago’s youth are the future of our city’s workforce. Yet not all of our young people are given pathways to participate.

It’s the problem Aon, a global professional services firm, and the City Colleges of Chicago set out to solve. In 2017, they pioneered a new apprenticeship program that recruits local high school graduates for positions that traditionally have gone to those with bachelor’s degrees. At the end of the two-year program, apprentices earn an associate’s degree, likely receive an offer for a full-time, permanent position, and graduate debt-free.

“At Aon we realized that our talent pool for smart, hardworking and dedicated employees is much, much larger if we go beyond recruiting those with four-year degrees,” said Bridget Gainer, Vice President of Global Public Affairs for Aon and a Commissioner on the Cook County Board. “Working with City Colleges is an important talent strategy, but it’s also an opportunity strategy: Chicago is a city ripe with opportunity and our all our young people should be able to attain it.”

Aon isn’t the only company implementing these programs and next year more than 400 apprentices will be working and learning and on the pathway to good paying careers.

“These apprentice programs are game changers,” said Juan Salgado, Chancellor of Chicago’s City Colleges. “They open doors to every single neighborhood in our city, and our students enter with a desire and drive to learn, grow and be a part of the workplace.”

It’s a strategy that’s making Chicago’s workforce more inclusive. “I believe everyone in our city, especially our young people, have a vision that’s more inclusive and less segregated than previous generations,” Chancellor Salgado observed. “If we listen to them and organize for their success, we’ll see them succeed at rates never seen before.”

2. Creating jobs and building wealth

“All of the areas that we work on are determinants of future wealth creation. Ultimately, when you get a certain level of education, your capacity to make money increases…We believe in focusing on the basic determinants of a good quality life.”

—Katya Nuques, Executive Director, ENLACE Chicago

All Chicagoans deserve the chance to create new opportunities and wealth within the new economy. Research shows that a 10 percent increase in metropolitan employment levels can raise average real earnings per person by approximately four percent, gains that are greater in percentage terms for African-Americans and lower-income individuals.[19]

While a growing economy provides the simple foundation for expanding opportunity and prosperity for all residents, the way the region grows has the greatest impact on inclusivity goals. For example, an advanced economy with pioneering industries and tradable sectors offers better pay and opportunities for upward mobility, yet female, African-American and Latino workers remain underrepresented in tradable industries and the STEM workforce.[20] Our policy recommendations ensure that all individuals benefit from economic growth through better quality jobs and increasing wealth

Workforce development for at-risk Chicagoans

“When people are blocking and tackling the challenges of poverty, they’re often times blocking and tackling all kinds of other stuff as well. Whatever their challenges, there are lots of them. So it’s not just about the job, it’s about the whole person.”

—Maria Kim, President and CEO of Cara

Drugs and gun violence have long plagued communities across Chicago, and West Side neighborhoods like Garfield Park and Austin have been the hardest hit by the spike in shootings.

Andre Campbell, a 20-year-old native of Austin, knows this narrative all too well. It was a road that he saw himself going down. “You see drug dealers and gangbangers where I’m from,” Campbell says. “That influenced me to get a job because I didn’t want to fall victim to the streets myself.”

In 2017, Campbell learned about Cleanslate, a social enterprise that provides paid transitional jobs to at-risk Chicagoans. It’s changed his life.

“I have a struggling family. We’re constantly trying to make ends meet,” he says. “Before this, I had nothing.”

Cleanslate is part of Cara, a nonprofit agency dedicated to strengthening communities. Since 1991, Cara has helped people affected by homelessness and poverty get back to work. Because securing a job is only the first step at finding real success and stability, Cara focuses on job retention and building the life skills of its participants.

“When people are blocking and tackling the challenges of poverty, they’re often times blocking and tackling all kinds of other stuff as well,” says Maria Kim, the President and CEO of Cara. “Whatever their challenges, there are lots of them. So it’s not just about the job, it’s about the whole person.”

Kim adds that while Cleanslate participants clean streets, the importance of their work goes beyond their daily tasks: They’re ambassadors for the communities in which they live and serve. For Campbell, the program has been a pathway to secure a full-time job in Environmental Services at Lurie Children’s Hospital, and he can now afford a place for him and his mom to live.

“What Cleanslate has meant to me is a better life and an opportunity to better myself,” he says.

-

Develop employer leadership to grow a pipeline of young skilled workers

Develop employer leadership in strengthening the talent pipeline.

Geography: City of Chicago and Cook County

“A lot of manufacturing jobs that used to be prevalent in this area are gone…they were low-skilled, but high paying jobs. We have a lot of people in our region that could benefit from workforce development.”

—Pete Saunders, Calumet City Economic Development Coordinator

Issue

High unemployment rates and low educational attainment are exacerbated by the concentration of poverty and crime in many segregated communities of color. According to UIC’s Great Cities Institute, the percent of youth ages 16 to 19 and 20 to 24 that are out of school and out of work, with no high school diploma, is 33.9 percent and 21.2 percent respectively, with African American and Latino youth more negatively impacted than white youth.[21]

Despite these bleak statistics, well-paid jobs exist. While recent reports cite the growing number of jobs in health care and in transportation and logistics (TDL), there is also difficulty filling many of these positions and a growing need to better connect both 1) neighborhoods to these clusters and 2) residents with the skill sets for jobs in these sectors.

On the workforce side, segmentation helps to identify the most promising pathways to living-wage employment. That is, the barriers to employment and work-readiness for “opportunity youth” (between the ages of 16 and 24 and neither in school nor working) may be worlds apart from the challenges for “middle skill adults” (age 25 and up, with some education and workforce experience). Both may be un- or under-employed, but likely have very different paths forward. High-risk disconnected youth often need immediate employment coupled with services and support to successfully sustain entry-level employment. Growing industries like health care and TDL often require industry-specific certifications that can be elusive due to required education thresholds, criminal background screenings and financial barriers posed by extended continuing education programs.

Recommendation

We echo the recommendation of JPMorgan Chase in its 2015 report, Growing Skills for a Growing Chicago: “Develop employer leadership in strengthening the talent pipeline. Industry leaders and the workforce system should coordinate to define joint goals for improving the talent pipeline and creating opportunities for career advancement. Employers should also invest in designing and implementing education and training programs that address their current and projected labor needs.”[22]

Every group we spoke with that is working intensively with opportunity youth said that they need a stronger commitment from the private sector to co-developing training and hiring graduates of their programs. Overall, we strongly recommend that the private sector elevates its board-level racial equity goals from supplier, service and employee diversity to also include a commitment to reducing Chicago’s violence through pathways to employment.

Case study

An initiative related to the Illinois Future Energy Job Act (FEJA) is an example of successful cross-sector collaborations to enhance job opportunities. Illinois partnered with ComEd to grant $30 million to six Chicago organizations to implement job training to prepare underserved residents for future energy jobs.4 As a result, the program aims to place 2000 new solar installers, increase access to electrical apprenticeships through IBEW instruction in targeted high schools and community colleges and support the incubation of new clean energy business owned and operated by people of color.

Impact

If even half of the 21,518 unemployed youth in Chicago obtained a job that paid somewhere between minimum wage and the median hourly wage ($19.31), then the local economy would see a boost of anywhere from $268 million to $432 million in wages. Furthermore, if these youth also obtained their high school diploma or equivalent, then they would each contribute $197,055 more dollars in average annual taxes paid over a lifetime of work (45 years) than if they had not received their diploma. In the aggregate, this would produce $2.1 billion for the local economy.[23]

-

Build wealth early through matched child savings accounts

Advance legislation to create a universal Child Savings Account (CSA) program in Illinois.

Geography: State

“Children’s Savings Accounts programs that automatically open college savings accounts for all children with a seed deposit, particularly when accompanied with matched savings for low-income families, can change the trajectory of a child’s life. They unleash children’s potential, support early childhood development, put them on a pathway to college and reduce the racial wealth divide”

—Jody Blaylock, Senior Policy Associate with Heartland Alliance

Issue

Research shows that child savings accounts have life-long impacts. Children with savings experience higher social-emotional skills, higher math and reading skills and an increased likelihood that they will attend and graduate college. Benefits are even greater for low- and moderate-income children: Children with even just $500 in college savings are three times more likely to attend college and four times more likely to graduate from college than low- and moderate-income children without savings.[24]

Yet, low-income families in Illinois face a number of challenges to building savings for higher education including having to cover other immediate expenses, debt repayment and gaps in financial education.[25]

Recommendation

The General Assembly should advance legislation to create a universal Child Savings Account (CSA) program in Illinois to automatically open at birth for every child born in Illinois.

How it would work

Heartland Alliance and the Illinois Asset Building Group, along with parent leaders and organizers statewide, led efforts to craft CSA legislation, introduced in 2017, based on recommendations generated by a bipartisan task force. Under this proposed legislation, every child born in Illinois would be provided a 529 college savings account. Administered by the Illinois State Treasurer’s Office, the accounts would be seeded with $50 and matched savings would be provided 1:1 for low-income families for up to $75 per year. Cities and counties could supplement this with additional matched savings, including partnering with philanthropic organizations to provide the match. These funds can used to pay for qualified post-secondary education expenses.

Impact

When targeted to low-income families, these incentives have a profound impact on increasing wealth in the region. According to an analysis of the proposed legislation, it could reduce the racial wealth gap for young adults by as much as 31.7 percent.[26] Estimates suggest cumulative savings accruing to existing low-income 18–34 year-old Bright Start beneficiaries would grow by at least $5 million. Even amongst the lowest-income Bright Start savers—those households making under $30,000 a year—adoption of the new program could result in average savings increases of $1,865 for Latino beneficiaries, and $1,855 for African-American beneficiaries.

-

Adopt a city earned income tax credit (EITC)

Establish a City Earned Income Tax Credit for working households to augment the pre-existing federal and state EITCs.

Geography: City of Chicago

Issue

The Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) was designed to help low-wage workers get ahead. Simply put, it is a key component of our nation’s safety net. Census data shows that in 2013, the federal EITC kept 6.2 million people, including 3.2 million children, out of poverty.[27] The success of the federal and state programs have been so widespread that a select few municipalities across the nation have adopted local EITCs to deepen its impact. New York City, Washington, DC and Montgomery County in Maryland have each implemented local EITCs, helping low-income working families keep even more of their hard-earned dollars. In the Chicago region, low-wage workers benefit from a federal and state tax credit, but would benefit even more by expanding the credit to the City-level.

Recommendation

Recommendation: Establish a City Earned Income Tax Credit for working households to augment the pre-existing federal and state EITCs.

How it would work

To create a local Chicago EITC, the Illinois General Assembly must amend the Illinois Income Tax Act 35 ILCS 5/212. Following the lead of other localities like New York City and Montgomery County, MD, a Chicago EITC could be administered through the state’s income tax process, adding a line that calculates a Chicago EITC as a percentage of the Illinois EITC. The credit would be refundable and eligibility guidelines would mirror the current state guidelines. Because the City of Chicago does not have an income tax, it would send reimbursement funding to the State, as it does for other streams of revenue and funding. To increase wealth-building potential, we recommend partnering with Center for Economic Progress and Bank On Chicago to allow for convenient, automatic deposit to a savings vehicle to build and/or repair credit and establish savings, such as an education savings account. A new City EITC should be paired with the state’s program for periodic payments, proven tools to avoid late fees and using payday lenders, as well as for building savings.[28] A graduated real estate transfer tax would not only cover the loss in tax dollars, it would provide a tax break to roughly 95 percent of the City’s homebuyers.

Impact

A 10 percent match of the federal EITC would put up to $600 annually back in more than 293,000 working families’ pocketbooks. Given estimates from Moody’s Analytics on the EITC’s “multiplier effect”[29]—the additional dollars spent throughout the regional economy from every dollar earned from the program—an extra $218 million in spending towards the regional economy on the part of working families would be added. The most recently available data suggests that in tax year 2014, more than 1.85 million New Yorkers received the federal EITC. When the federal, New York State and New York City benefits were combined, the average benefit to working families was over $2,900 per household[30]

However, in Chicago millions in potential EITC income currently goes unclaimed. An analysis of EITC eligibility filing in 2014—the most recently available data year—reveals that of all community areas, West Lawn, Ashburn, South Lawndale and North Lawndale had the highest number of eligible households. If Chicago had an EITC, assuming a filing rate on par with the state’s (79 percent), we estimate that residents in these 4 areas could receive an additional $11 million in tax credit beyond their federal and state returns.

-

Make jobs accessible to low-income residents

First, pilot new services in the Chicago region to improve connectivity between employment hubs and low-income communities with low employment.

Geography: Chicago Region

“When you are talking about transportation equity, you need to look at the amount of time it takes to get from point x to point y. Some low-income workers are doing one-to-two hour commutes to get to work and the same to get back.”

—David Luna, Executive Director, Equal Voice Action

Issue

Many of the region’s low-income residents struggle getting to and from their jobs. Car ownership is low and transit options may be limited, slow or not serve relevant employment destinations. Four of the five largest employment centers in the region are poorly served by rapid transit and major employment centers rarely overlap with economically disconnected populations. To support economic mobility in our region, we need new, flexible transportation services that connect underserved populations with employment hubs, especially in suburban areas.

Recommendation

Pilot new transit services in the Chicago region to improve connectivity between job hubs and low-income communities with low employment. In addition, collaborate with workforce development service providers to determine transportation needs and address them.

How it would work

Workforce boards provide counseling and coordinate job placements for individuals who struggle finding employment. Transportation is often a major factor determining which jobs workers can access; long and difficult commutes affect job retention. Conducting focus groups with workforce board counselor and client groups, as well as analyzing data on where people live and work, would help identify specific mobility needs and gaps in knowledge by counselors and job seekers. Once needs are determined, enhanced transportation training for counselors can be developed, potentially through RTA’s Travel Training program. Additionally, with new information about worker needs, new customized transit services can be developed such as providing last-mile transportation from the endpoints of CTA lines and Metra stations.

Work with employers in areas without good fixed-route transit service or lacking last-mile connections to develop new reverse-commute, suburb-to-suburb routes or last-mile service through partnerships with Pace or private on-demand providers such as Chariot or Via. Work with employers to develop new types of partnerships to enhance transit service and supportive pedestrian infrastructure along arterials where there is employment. Additionally, develop services connecting with termini of CTA lines, such as at the Rosemont Blue Line transportation hub, from which workers need last-mile access to suburban employment.

Case study

Transportation Management Association of Lake-Cook: According to the 2017 Annual Report, shuttle service is provided on 13 routes, serving 40 companies to Metra stations on the Milwaukee North, Union Pacific North and the Union Pacific Northwest lines. Ridership for 2017 totaled over 1,000 daily trips.

Impact

Based on TMA of Lake-Cook results, services along another job-rich corridor could provide last-mile transit access to hundreds of employees.

-

Establish a fairer way to pay for transit

Implement a capped fare system at CTA, Metra and Pace to benefit low-income riders.

Geography: Chicago Region

Issue

Low-income riders who do not qualify for discounts often struggle to buy a weekly or monthly pass and instead pay for transit as they go, foregoing the discount that comes with bulk purchases. Riders who can’t pay upfront for a $105 monthly pass or $28 weekly pass pay the full fare for every ride and never reach the “free zone” that monthly pass riders have access to.

Recommendation

Implement a capped fare system for the Chicago Transit Authority, Metra and Pace to better serve low-income riders.

How it would work

A fare-capping system would mean that once a Ventra user buys enough single rides within a fare pass period (e.g., week or month) to equal the value of a pass, rides during the rest of the period would be free. This enables frequent riders who cannot afford the upfront cost of a weekly or monthly pass to pay in installments by single-ride payments. The State of Illinois should cover the reduced revenue from any new discount as part of its current program to reimburse CTA, Metra and Pace for fare discounts for persons with disabilities, students, Medicare card holders and military personnel. Unfortunately, the State of Illinois has not fully reimbursed the transit agencies for the past several years,[31] creating a funding shortfall, so a stable reimbursement schedule would be need to be ensured to initiate such a program.

Case study

In response to grassroots pressure for a more equitable fare structure, Trimet in Portland is the first major American city to enact a fare capping policy, according to TransitCenter. International transit agencies in cities including London and Dublin have used fare capping for over a decade.

Impact

Anyone whose pay-as-you go transit fare spending exceeds the cost of a weekly or monthly pass will limit transit expenditures to the cost of a pass, which will lower transit costs for some and increase predictability of expenditures.

Affordable housing builds strong communities

Homeowners Maria Cruz Espino and Fabian Espino talk about their experience with the New Homes for Chicago program with Raul Raymundo (center), CEO of The Resurrection Project.

When Maria Cruz Espino and Fabian Espino moved into their brand-new Pilsen home in 1997, they could barely believe their good luck. “The girls were so excited, choosing their rooms,” Maria says.

The Espinos purchased their four-bedroom property through the New Homes For Chicago initiative, launched in 1990 by the City of Chicago to provide low- and moderate-income working families with the opportunity to buy high-quality new houses.

New Homes facilitated the development of city-owned vacant land for low-cost, new housing and provided subsidies for both developers and homebuyers. What once were vacant lots became the sites of families’ dreams.

But the Espinos’ home offered more than a safe, beautiful place to rest their heads. Homeownership is the single greatest wealth-building vehicle for people of color in America, and the Espinos’ property allowed them to grow their assets.

“Many working families do not invest in the stock market. One of the few vehicles by which they can build wealth is by becoming homeowners,” says Raul Raymundo, longtime CEO of The Resurrection Project, a community development non-profit founded in 1990 in order to fight blight and crime in Pilsen.

Through the years, Maria and Fabian watched their children grow up and go to local universities, one by one. They’ve planted tomatoes and jalapeños in their garden while they’ve put down deep roots in Pilsen, a community where rising prices threaten to displace many longtime residents.

Now, more than ever, as prices rise, investments like New Homes For Chicago are critical for Chicagoans. Raul, Maria and Fabian agree: New Homes For Chicago worked for Pilsen, and it can work again.

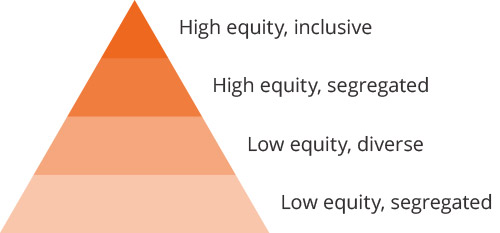

3. Building inclusive housing and neighborhoods

Nationwide, only one in five households eligible for housing assistance receives it,[32] and the limited tools that we have to produce quality, affordable housing are increasingly in jeopardy. At the same time, the Obama Administration’s 2015 rule on Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing[33] mandated—nearly 50 years after the Fair Housing Act—that municipalities and public housing authorities receiving federal dollars cannot use those funds to perpetuate concentrated poverty.

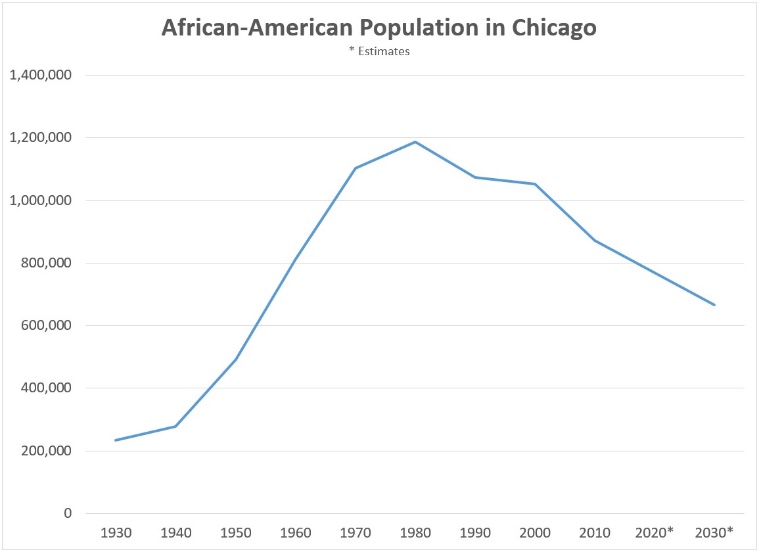

Throughout the Chicago region, low-income renters and homeowners face the risk of displacement as neighborhoods change or continue in a troubling direction. Some of this displacement comes from rising property values due to gentrification and corresponding increases in rents and property taxes. In other instances, communities are experiencing displacement due to disinvestment: people of color are leaving long-disinvested communities for other parts of the region and country due to inadequate funding for key infrastructure and institutions, including schools, community spaces and health centers.

Our recommendations recognize the need for affordable housing and inclusive community investments across our region, both in opportunity areas and disinvested communities, and everywhere in between. Our approach targets everyone and all communities within our region.

Community organizing unlocks the talents of local residents

James Rudyk, Jr. and Dominica McBride empower residents to take a more active role in their communities.

Belmont Cragin is changing. The neighborhood on Chicago’s northwest side was once deeply Polish, but now is the fastest growing Latino community in the city of Chicago.

Neighborhoods change faster than policies, knows James Rudyk, Jr., Executive Director of the Northwest Side Housing Center (NWSHC), a local non-profit organization that has worked since 2003 to offer housing counseling, financial education, outreach, advocacy, supportive services, and—perhaps most importantly—community organizing.

“Residents are in the best position to create and lead change because they best understand their community,” says Rudyk. “The days of top-down community development are over. For us, it’s about coming from the grassroots, not the grasstops.”

For Rudyk and NWSHC, the lessons gleaned from community organizing inform a shifting suite of relevant programming, from first-time homebuyer classes, to foreclosure prevention counseling, to a Latina-centered financial education program. The NWSHC provides services in English, Polish, and—increasingly—in Spanish.

“It’s not acceptable to exclude 80% of the Belmont Cragin community that’s Latino,” Rudyk says. “We can no longer accept that.”

Dominica McBride, Founder and CEO of Become: Center for Community Engagement and Social Change, is working with NWSHC to build the organization’s long-term plan in a way that listens to needs, desires, and lived history of locals. McBride ensures that all voices are heard during the organizing process.

Both McBride and Rudyk see that unlocking local residents’ power through organizing offers a potent model for building equity across Chicagoland’s deeply divided neighborhoods.

“We can do this across the city,” McBride says. “We can get across and through that gap that segregation creates and start to be together.”

-

Lessen local control over affordable housing decisions

Ensure that all communities contribute to the city’s affordable housing needs. Specify that the selection criteria in the Qualified Allocation Plan cannot include consideration of any support for or opposition to a project.

Geography: Chicago, state

“If we don’t really think about putting policies in place that preserve affordable housing in areas of opportunity, we will continue to add to the segregation of this city.”

—Diane Limas, President, Communities United

Issue

Nearly half of adults living in Chicago are spending more than they can afford on their homes or apartments.[34] This cost burden and shortage of affordable housing—especially for low-income residents—is experienced in all 50 wards and 77 community-areas spanning the city of Chicago. In higher-cost areas, the shortage is particularly stark due to local and political opposition, higher costs for land and zoning laws that limit multi-family development. Of the 1,623 affordable housing units created by the Affordable Requirements Ordinance (ARO) and Density Bonus fees through 2015, there were zero in nearly two dozen North, Northwest and Southwest side community areas.[35] Evidence shows that the greater the level of involvement by local government and residents in development approval, the greater the segregation.[36]

At the state level, in order to receive Low Income Housing Tax Credits in support of an affordable housing development, developers must make efforts to obtain some form of local support for the project. This requirement can open developers to significant challenges in advancing a project and potentially deter them from completing the project altogether.

Recommendation

At the city level, when a residential development with at least 10 percent affordability is proposed in a ward with less than 10 percent affordable housing, the proposed development can no longer be rejected or delayed indefinitely by the Alderman alone. At the state level, remove any requirement from the Qualified Allocation Plan around obtaining local support for projects, including letters of support and certifications of consistency with the Consolidated Plan.

How it would work

If a development with a minimum of 10 percent affordable units (targeted at households earning up to 60 percent AMI) is proposed in a ward whose housing stock is less than 10 percent affordable, then the proposed development would automatically go through a streamlined process for approval. In this process, the Alderman can still shape the development and request changes, but no longer has veto power. Enacting a streamlined process would also ensure that projects don’t languish simply by dragging them out over long periods of time, forcing developers to abandon their plans without ever actually being told no.

Impact

While initially supportive of the project, in late 2017 a Northwest Side Alderman began to voice his opposition to a planned 297 unit housing development in his ward, 30 units of which would have been designated as affordable. At his request, the project has been delayed indefinitely. Based upon the work of economist Raj Chetty to quantify the benefits of affordable housing for children of low-income families, we estimate that the loss of affordable housing associated with the project amounts to a loss of ~$762,702 in lifetime earnings, and $135,315 in lost lifetime tax revenue for the would-be beneficiaries. These calculations assume that would-be families in the 30 affordable units would include ~7.7 children under age 8, and ~12.08 children under age 13 as the immediate beneficiaries.

Case study

Effective January 1, 2018, California’s Senate Bill 35 mandates cities that have not yet met affordable housing targets to streamline and more quickly approve developments including minimum levels of affordability, even if there is local opposition to them. As the bill’s fact sheet explains:

When local communities refuse to create enough housing—instead punting housing creation to other communities—then the State needs to ensure that all communities are equitably contributing to regional housing needs. Local control must be about how a community meets its housing goals, not whether it meets those goals. Too many communities either ignore their housing goals or set up processes designed to impede housing creation.

-

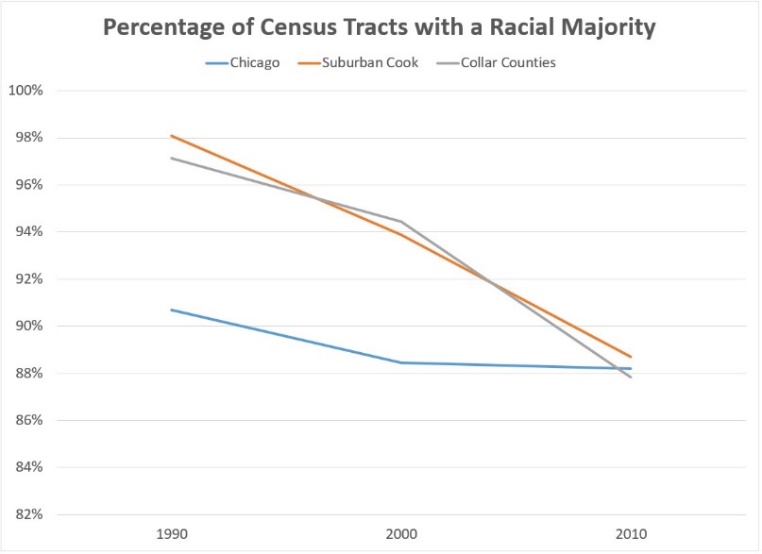

Conduct a regional assessment of fair housing

Conduct a regional Assessment of Fair Housing that coordinates across regional jurisdictions.

Geography: Chicago, Cook County, ultimately region

Issue

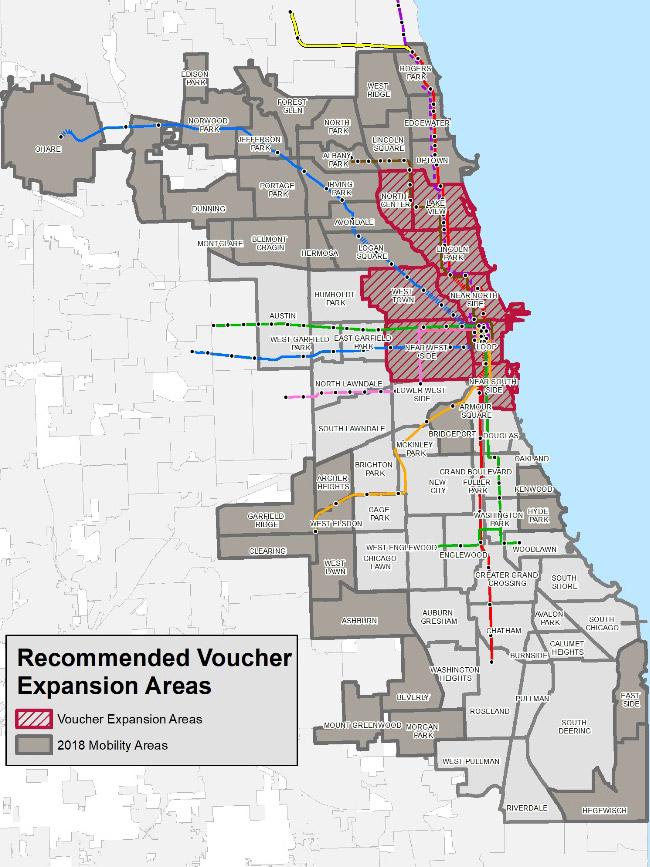

In 2015, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development issued a new rule—and a mapping tool—to help communities address segregation. The new rule requires that any HUD-funded entity must identify the factors that limit the choices of where people live, conduct an analysis of segregation and provide a plan to combat it. The goal was to put measurable standards behind the Fair Housing Act, which affirms that municipalities that receive federal funds for housing must invest them to achieve two keys goals: more opportunities for low-income families who desire to move to high-opportunity neighborhoods and improve areas that experience segregation and disinvestment