Opportunities for Integration in Chicago Public Schools Are Rare—and Too Important To Miss (Part II)

In this series, the Metropolitan Planning Council (MPC) will explore recently profiled opportunities for small pockets of increased integration within Chicago Public Schools.

If our focus thus far has been on steps that Chicago Public Schools could and should take, it is not to ignore the importance of the individual decisions we all make and mindsets that we have.

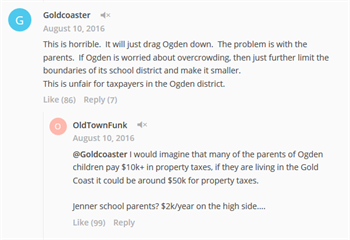

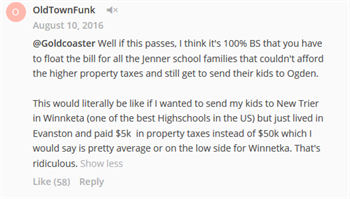

Consider the hot-button issue of the merger of Ogden (diverse, with many high-income whites) and Jenner (primarily low-income, African American) elementaries. DNAinfo sought opinions on the merger last September, and comments continue to roll in. A particular exchange of recent comments (below) caught our eye.

This line of thinking represents the view that one’s property taxes should go to one’s neighborhood school only, almost as if property taxes were akin to private school tuition.

As we’ve written about before, the fact that school quality is “capitalized into housing prices”—in other words, the cost of admission to high-performing neighborhood schools is a high real estate price point—has apparently led parents such as Goldcoaster and OldTownFunk (and the dozens who’ve agreed with them) to think they’re entitled to something they are not.

And no, OldTownFunk, comparing Ogden and Jenner is not “literally” the same thing as Evanston Township High School and New Trier. The difference here is more than semantics: Chicago Public Schools is one unified district. That means that the quality of education should be roughly equivalent across the district.

You pay more in property taxes because your home is worth more than most across the city, not because your child is more worthy of a quality education than other children across the city.

Clearly, parents such as those quoted above feel they paid for their boundaries as they are, and the political pressure they can assert is intense.

What is Chicago Public Schools’ obligation to parents in this and other scenarios covered by WBEZ? Is changing the admissions boundaries or merging with another school somehow an abdication of an unwritten contract to provide the school unchanged in perpetuity? If so, are the 50 neighborhood schools closed in 2013 in breach of the same contract? When we closed those schools, we asked thousands of black and brown families to adjust. Will we not ask the same of white parents?

Of course, parents across the board—from the 50 school closures to a single proposed merger—have the right to have their questions answered and their concerns addressed. As UCLA Civil Rights Project director and longtime school integration scholar Gary Orfield puts it:

“Parents have the right to know the school is secure and the teachers have been trained and nothing’s going to be done to the quality of the instruction. But they don’t have any right to preserve an enclave of privilege and they shouldn’t be fearful of coming in contact with poor kids.”

You pay more in property taxes because your home is worth more than most across the city, not because your child is more worthy of a quality education than other children across the city.

With the right supports—and the importance of this cannot be overemphasized —for families, students and school staff, this change could be a win for all involved in each of the integration scenarios that WBEZ explored. Education research has shown repeatedly that diverse school settings benefit not only low-income students, but middle- and upper-class students as well.

Integration alone does not automatically lead to these benefits. In order for school integration to meaningfully benefit all children, and in particular low-income children, all parties involved need training on implicit bias, teacher perception and systems in place to ensure that parents of all incomes are on equal footing in influencing and setting school policy.

In the WBEZ report, people in leadership claim that addressing segregation is not their job. They are not alone; at a meeting where she rejected parent-led efforts to combine attendance boundaries for two segregated but nearby schools, New York City schools chancellor Carmen Fariña made clear her view that school integration must be achieved through the choices individual parents make. Citing residential segregation, Seattle’s school board chairwoman told the Seattle Times that “It’s not my job to desegregate the city.”

These are curious conceptions of what segregation is and how it works, and the role of systems to change the environment in which individuals make decisions. Segregation is the separation of humans into ethnic or racial groups in daily life. It is not a nebulous thing “out there” that other people do, and over which elected officials and school and housing leaders have no impact. Rather, segregation is created and maintained by decisions that we all make—both at the small individual level and the larger policy level by people in positions of power—to perpetuate or exacerbate the status quo of separation by income and race.

A view that focuses only on what a school board should do differently to achieve more integration misses the role of individuals and the need for them to see themselves as part of a whole. A view that emphasizes only individual family decisions, on the other hand, loses the importance of creating as many opportunities for high-quality, integrated schools as possible.

Our view is that when a community’s demographics change, and we have a rare opportunity to create schools that are racially and economically integrated, there is an imperative to push to make the opportunity work.

Upending educational segregation is very hard. All the more reason to seize proximate opportunities where they exist. If not in these spaces and not now, then where and when?