One Reason Chicago Is Growing More Slowly Than Other Cities: Household Size

Other cities are seeing more families move in, which means a higher population count than if singles are moving in.

Given all the gloom and doom I’ve written about Chicago’s growth, where do all of the new corporate headquarters moving to Chicago or the billions in real estate being developed fit in? Data from United Van Lines shows that of the 100,000 moves handled by the company across the nation in 2014, Chicagoland took the top spot. Chicago is an attractive place for many people. So why is our population growth lagging? Household growth data points to an answer.

While recently analyzing why Nashville grows by as many people in one day as it takes Chicago to in one year, I dug into what kinds of people are choosing Nashville: Is it singles? Married couples without children? Families?

I found something interesting in the household data. From 2009 to 2014 Chicago grew by the same number of households as Nashville—about 17,000—but Nashville’s population grew by 41,000 people compared to Chicago’s 23,000 people—roughly double.

What?

Well, the makeup of those households was significantly different. Chicago’s 17,000 households were almost all—96 percent—non-family households: singles or people living together that are not related or not married. Meanwhile, Nashville’s 17,000 households were majority family households. So Chicago has brought in smaller households; likely singles are moving to the city or larger families move out and are replaced by a single person or a non-married couple with no children. While in Nashville, household growth is families, likely with children—and that means more people per household and more citywide population growth.

Nashville’s cost of living is much lower than Chicago’s and the city has a slower pace of life. So that’s one reason more families would choose the Music City over the Windy City. But how about other cities? Or cities with the same or higher cost of living?

Analysis of population growth for the top 20 most populous cities in the nation show over the past five years, many had similar household growth numbers as Chicago—but more population growth.

Of the top 20, most had higher rates of family household growth than Chicago, especially those cities whose population grew above 5 percent. Which makes sense because family households tend to be larger than non-family households.

And cost of living isn’t the answer. A scan of large and mid-size peers show that even places with a similar or higher cost of living than Chicago—Los Angeles; Seattle; Washington, D.C.; San Francisco—grew by more family households.

A city should strive for balanced growth. So having 96 percent of all household growth in the non-family category is an issue.

How do we attract more families? We build better communities across the entire city.

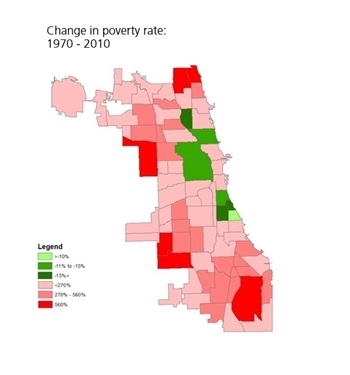

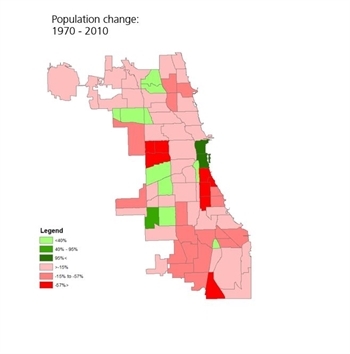

That means tackling this fact: Since 1970, nine neighborhoods in Chicago have or are gentrifying, while 45—up from 29 in 1970—are impoverished.

And the data show that since 1970, neighborhoods in Chicago that have lost population are those that have had an increase in poverty.

Metropolitan Planning Council analysis of U.S. Census data

As my colleague Marisa Novara points out, “We’re all paying a steep price for the status quo.” The Metropolitan Planning Council has begun analyzing the cost of that status quo and is working with local community, business, policy and governmental leaders to identify and help implement cost-effective solutions to shift this trend.

We can start by investing to make all of our neighborhoods more attractive for everyone. Having more transportation options for getting to work for all residents; integrating affordable workforce housing in new developments, not just in places of poverty; and prioritizing infill redevelopment, especially around transit and our existing infrastructure are all good steps toward a more robust growth rate in the region. Moving people out of poverty will help build better communities throughout Chicago, making them more attractive for all types of households—singles and families.