The Basics on Lead in Drinking Water

This is the first in a series of blog posts that will explore solutions to the complicated issue of lead in drinking water.

Check out the other posts in this blog series:

- Helping Illinois child care centers reduce exposure to lead in drinking water

- Putting the whole lead in drinking water thing into perspective: a water professional weighs in

- Buffalo, NY: A Rust Belt City’s new approach to tackling lead in drinking water

We don’t know the extent of Northeastern Illinois’ lead problem.

Many muncipalities in our region have lead service lines in their drinking water systems, especially older and long-established cities. For example, recent reporting revealed that an estimated 70% of homes tested for lead in tap water tested positive in Chicago, and many Chicago Public Schools and Chicago Park District drinking fountains are affected as well.

As part of our Water Supply work, Metropolitan Planning Council and partners have been working behind the scenes to address policy and infrastructure issues related to lead in drinking water. Here’s what you need to know.

What is lead, and what’s so bad about it?

Lead is a naturally occurring heavy metal which can be found in soil, air, and water. Due to its properties such as malleability, it has historically been used in many commercial and industrial products such as paint, plastics, pipes, gasoline and cosmetics. It’s also what’s in those heavy x-ray aprons at the dentist!

While a useful material, lead is harmful to humans. Children are the most susceptible to the effects of lead poisoning, which can lead to decreased IQ, hyperactivity, hearing problems, stunted growth and learning disabilities. Lead also affects adults, in whom exposure increases the risk of heart attack, high blood pressure, kidney failure and reproductive problems for both men and women.

The negative effects of lead are caused by ingestion—drinking, eating or breathing it—and most often accrue over time rather than suddenly. While lead is technically safe to touch, making contact can often lead to unknown ingestion (for example, touching lead dust then absent-mindedly touching your mouth). While acute symptoms of lead poisoning can be treated, long-term physical and mental damage cannot be reversed.

Even in cases where lead poisoning has a small effect on an individual (e.g. a small decline in IQ), if it is widespread enough in a community, it can have large costs across a society, such as medical care, education, criminal justice and overall economic loss.

Levels of lead inside a person are measured through blood lead level. There is no blood lead level above 0 considered risk-free, in fact, both the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) believe there is no safe level of lead exposure. However, due to its natural occurrence and difficulty of removing lead sources, the CDC uses certain thresholds as advisory levels for intervention.

How does lead end up in drinking water?

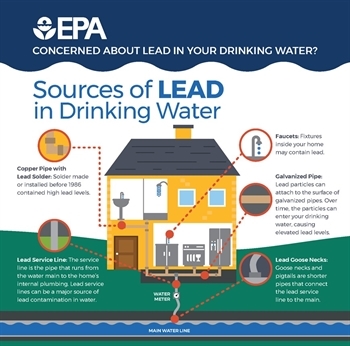

While paint, dust and soil are the most common sources, lead can also be found in some water pipes inside buildings or pipes that connect buildings to a water main (service line). Lead found in tap water usually comes from the decay of old lead-based pipes, fixtures or from leaded solder that connects drinking water pipes.[1] [2]

Lead pipes have been used since the invention of water service in ancient Rome. This metal is well suited for making pipes because it’s stable and easily malleable. The only major problem is—it’s poisonous. Lead pipes have been used throughout the U.S. since the 1800’s to supply drinking water. It is estimated that by 1900, more than 70 percent of cities with 30,000 or more residents were using lead-based products for conveying water.[3] Due to its toxicity, many U.S. cities began moving away from using lead pipes by the 1920s. However, due to strong lobbying efforts from the lead industry, national plumbing codes did not outlaw the use of lead pipes until the 1980’s when Congress finally banned the use of this toxic metal to convey drinking water.[4] While this ban greatly decreased the use of lead in new plumbing materials, it did not require remediation of older plumbing infrastructure.

US EPA

What is happening with lead in drinking water today?

The water crisis in Flint, MI was created when a change in water supply coupled with a lack of proper treatment caused corrosion of pipes. This caused Flint’s soaring and dangerous lead levels in their water. While our region’s lead problem is not due to negligence, there are concerns about lead in drinking water infastructure. In fact, Chicago has more lead service lines than any other city and actually required them by law until 1986, when federal Congress banned its use. However, Chicago is not the only municipality that has lead service lines in Northeastern Illinois.

Why don’t we just replace the lead pipes already?

The issue of lead pipes, fixtures and solder in our drinking water infrastructure is a complicated one. Here are a few basic reasons why we can’t just replace everything in one fell swoop.

- We don’t know where the lead pipes are. It is unknown just how many lead service lines a community might have since installation or replacement of these pipes has not been well documented or mapped—so inventories must be done to identify risk and solutions for communities.

- We don’t agree on who’s responsible for remediation. Most service lines (pipes that connect a building to a utility water main) are at least 50% if not 100% the responsibility of the property owner (not the municipality or utility). Disagreements abound about whose responsibility it is to fix lead service lines or ensure that pipes, fixtures and solder inside a privately-owned building is lead-free.

- Remediation is expensive. Estimated costs to replace a full lead service line can run anywhere from $5,000—20,000 depending on the municipality and various site-specific considerations. Replacing existing lead service lines will be costly, and there is an equity issue to consider here since lower income households will be at a disadvantage without assistance.

- Replacing service lines doesn’t necessarily fix the problem. Even if all existing lead service lines were replaced, there would be no guarantee the concern of lead exposure in water was solved completely since buildings might still have old fixtures or solder that contains lead.

Regardless of how complicated the situation is, not attending to this public health issue is not acceptable—we need action today.

Where do we go from here?

Everyone (including politicians, the general public and the water industry) can generally agree getting rid of lead pipes and fixtures in our drinking water infrastructure is good and needed. However, the lack of regional discussion and action on this issue is concerning. There are legislative efforts at the state-level. In 2017, Illinois passed a bill requiring more extensive testing for lead in drinking water in schools and daycares, and there have been recent draft bills that would require all drinking water utilities in the state to identify, map and create a plan for replacing lead service lines in the communities they serve.

Lead in drinking water highlights regional equity, sustainability, prosperity, public health and engaged and responsible governance—core values of MPC. As a non-profit, regional policy change organization, MPC will be working to bring productive dialog, collaborative efforts, research and storytelling, best practice resources, pilot projects and policy advocacy to provide viable solutions to our lead in drinking water issue.

To kick off this public dialog and body of work, please join us for an MPC Roundtable on October 30, 2018 that will feature case studies of how some communities are tackling this issue, and what are helpful pathways for equitable funding and financing: Lead in Drinking Water: It’s Time to Get the Lead Out. We look forward to seeing you there.

References:

[1] Environmental Protection Agency. EPA in Illinois. Advice to Chicago Residents about Lead in Drinking Water. Source: https://www.epa.gov/il/advice-chicago-residents-about-lead-drinking-water.

[2] Centers for Disease Control. About Lead in Drinking Water. 2015. Source: https://www.cdc.gov/nceh/lead/leadinwater/.

[3] Fluence Corporation Limited. A Very Brief History of Lead in Water Supplies. 2016. Source: https://www.fluencecorp.com/brief-history-lead-water-supplies/.

[4] Rabin R. The lead industry and lead water pipes “A MODEST CAMPAIGN” Am J Public Health. 2008. Source: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2509614/.