Chicago region missing the mark on sidewalk accessibility planning

Last year, we celebrated the 30th anniversary of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). Much of the ADA addresses issues of equal access for people with disabilities. One part requires units of government with more than 50 employees to conduct an inventory of physical barriers to access in the public right-of-way (think streets and sidewalks) and make an ADA transition plan to remove them. In February, I wrote about what an ADA transition plan is and why it’s important. A transition plan could address items such as missing curb ramps, obstructed sidewalks, or a lack of safe crossings. It’s a planning tool that holds huge potential to improve access not just for people with disabilities, but entire communities.

But there’s a problem; despite the federal requirement, transition plans are an underused tool. And as a result, 30 years after the Americans with Disabilities Act passed, many barriers to access still exist. A national study of 401 government entities found that only 13% had transition plans readily available.

So what’s the state of transition planning in Chicagoland? We at the Metropolitan Planning Council wanted to know how many communities in our region have transition plans, and their caliber. We partnered with the Great Lakes ADA Center at the University of Illinois-Chicago to find out, and we’re sharing the results in a new report called Where the Sidewalk Ends: The state of municipal ADA transition planning for the public right-of-way in the Chicago Region.

Inventory results

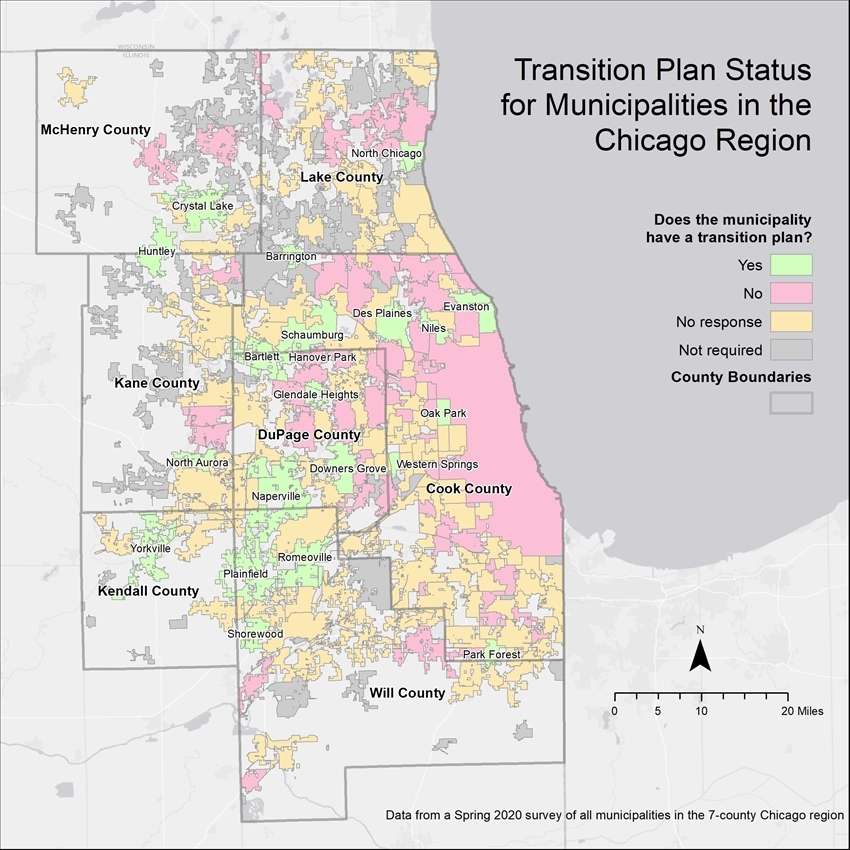

The first step to answering this question was tracking down all the transition plans in the region. These plans are legally required to be available to the public, so one might expect locating them to be relatively easy, but it was not. We worked with a group of students from the UIC College of Urban Planning and Public Administration to contact each of the 200 municipalities in the region with at least 50 employees. Of the 83 municipalities that responded, only 22 had a transition plan. That’s just 11%.

It’s important to recognize that this inventory is just a snapshot in time. It’s possible that we missed a few, and some may be in the works currently. But that would likely only move the needle by a few percentage points, and this figure is in line with the national study that found a 13% compliance rate. Of the plans that we were able to verify, they had a pretty wide distribution with no clear geographic pattern.

The students also assessed the quality of the plans by checking to see how many of the five required elements each plan satisfied. As you can see in the table below, none of the required elements were satisfied universally by all 22 plans. The most essential task of a transition plan, completing an inventory of access barriers, was done for all but one plan, and nearly all plans specified a responsible public official. Most described the methods by which the barriers would be removed. However, only half went a step further and actually included a schedule for when barriers would be removed and/or deficiencies corrected. Only half of the plans had even superficially involved the general public, much less had a robust engagement process.

| Required Element | Count | % |

| Complete an inventory of barriers in public rights of way | 21 | 95% |

| Identification of a public official responsible for plan implementation | 20 | 91% |

| Describe the methods that will be used to remove barriers and make facilities accessible | 18 | 82% |

| Include a prioritized schedule for barrier removal | 11 | 50% |

| Provide an opportunity for interested persons to participate in the development of the plan | 11 | 50% |

Going above and beyond

The five required elements make up the bare minimum of what must be included in a transition plan. In reality, plans vary widely in detail, quality, and comprehensibility. Experts have identified best practices for transition plans that make them more representative of a community’s needs and more likely to be implemented. The students checked the plans for 35 total elements, including the five required elements, across six categories to see where the region’s strengths and weaknesses lie.

The plans were generally strong on developing a thorough inventory of access barriers and designating a high-ranking official to implement the plan. They were much less consistent with regard to public participation, describing their barrier removal methods, or providing a schedule for improvements. Unfortunately, these three latter categories are where some of the most important work happens.

Community characteristics

Creating an ADA transition plan takes time, money, and expertise. These resources are not evenly spread across communities in the Chicago region, and these inequities likely has an impact on a municipality’s ability to create a high-quality transition plan. To investigate this idea, we looked for a relationship between municipal transition plan status (whether they had a plan) and certain demographic and community characteristics. For municipalities with plans, we also investigated if those same characteristics might correlate with the quality of their plans. We found that:

- Larger municipalities and municipalities with higher median incomes were more likely to have ADA transition plans.

- Municipalities with a higher percent of people with disabilities were less likely to have a transition plan than those with a low percent of people with disabilities.

- Among municipalities that did have plans, higher rates of disability were associated with lower plan quality, meaning that they satisfied fewer required elements and adhered to less of the expert-identified best practices.

- Municipalities with higher median incomes tended to have higher quality plans.

- The municipalities with the highest percentage of Black residents and people of color had completed significantly fewer required elements and best practices in their plans.

Moving forward

Like the nation at large, our region hasn’t done a great job at creating and implementing ADA transition plans. That doesn’t mean that local governments haven’t been working hard to make their communities accessible, but they haven’t done it in a systematic, transparent, and community-driven way. Among the municipalities that did complete a plan, most had very cursory public outreach, and a surprising number had no obvious means for public comment at all. It’s also unclear how seriously officials took the process beyond satisfying the minimum requirements. There is very little information about implementation and future updates. Additionally, as with all other areas of planning, there are clear equity issues. Lower-capacity communities are struggling to make these plans impactful, or just make them at all.

Fortunately, for the nearly 90% of eligible municipalities in the Chicago region that don’t have an ADA transition plan, there’s a lot of great information on how to get started. In the last of this three-part blog series, I’ll share some of the resources available to local governments.