An Ecosystem Approach to LSLR Affordability

The 2021 federal Bipartisan Infrastructure Law made a landmark investment in lead service line replacement (LSLR), authorizing $15 billion in funding specifically for removing lead pipes. States, who will distribute this funding through their State Revolving Fund programs, must now answer a question: how can states best distribute LSLR funding to enhance affordability for households?

In this blog post, I outline one piece of an answer to this question. I argue that a holistic analysis of LSLR affordability is needed to guide state allocation of federal LSLR funding. I will call this analysis the “ecosystem approach to LSLR affordability.” I use the term “ecosystem” to signal that paying for lead service line replacement is part of a large web of interconnected costs and capacities.

I lay out some key considerations in developing this approach:

- Scale of affordability

- LSLR cost within a community (LSLR burden)

- Additional community costs

- Capacity of a community to pay for LSLR

- Effect of state distribution of federal funding on LSLR affordability

This ecosystem analysis would require complex modelling to determine how all the relevant components interact. Developing this tool would go a long way in identifying how policy can intervene in LSLR affordability.

Policy Context

An analysis of LSLR affordability is needed because federal funding for LSLR is arriving but is scarce in many states; it is crucial that funding is prioritized for communities that can least afford LSLR. Illinois – where I live – serves as a good example of a state where federal resources are limited. Illinois has nearly 1,800 community water supplies. All of them are required by state law to replace their lead service lines on a timeline ranging from 15 to 50 years starting in 2027. According to a 2023 report of the Illinois Lead Service Line Replacement Advisory Board, the estimated total cost of replacement in Illinois will exceed $5.8 billion; that same report estimates Illinois will receive just over $1 billion in federal lead service line replacement funding. How should Illinois prioritize distributing existing federal funding to maximize LSLR affordability?

It is largely up to individual states to determine this prioritization. The Illinois Environmental Protection Agency has developed a prioritization score that enlists a range of criteria, including poverty rate, lead service line burden, and median household income. These criteria offer a strong starting place for determining where federal resources in Illinois should be prioritized.

Strong as this foundation is, there is more work to be done to understand the complex relationship of LSLR to affordability. Communities face additional costs beyond LSLR that may strain financial capabilities, and these additional factors are frequently not included in discussions about LSLR affordability. Just on the capital side of water utility costs, communities may be paying for water and sewer main replacements, new pumps, and treatment technologies to address emerging contaminants.

Households, too, experience the cost of LSLR not in isolation, but as one of many expenses they incur in their lives. There are not only water bills, but housing payments, transportation costs, and childcare costs. The affordability of LSLR for households will depend on this broader context, and on how different revenue mechanisms pass those costs onto residents.

Ecosystem approach to LSLR affordability

What is needed in this context is an analysis of LSLR affordability that looks holistically at the diverse costs and capacities communities carry with them in paying for LSLR. In other words: the degree to which LSLR is affordable will depend on what else needs to be paid for and what’s available to pay for it, in addition to who ultimately bears the cost and how. This is the broader “ecosystem” in which LSLR affordability operates.

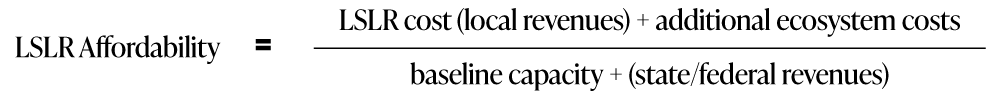

Here is a first attempt at capturing this concept as an equation. Warning: I am no economic modeler! But hopefully this will offer some insight into how the relevant components might fit together. The lower the affordability score, the less affordable LSLR will be for households in a given community:

I place municipal and state/federal revenues into parentheses to signal that they are policy interventions whose effects would be projected.

I think this is ultimately an intuitive approach, that LSLR is part of a broader portfolio of expenses and capacities. Below, I outline some of the core elements that would need to be addressed in developing a systematic model of this concept.

1) Scale of LSLR affordability

Thinking about LSLR affordability means thinking about who LSLR will be affordable for. This means thinking about scale. Throughout this analysis, I will focus on household-level affordability in relation to community affordability.

LSLR affordability needs to take as its starting place household-level affordability because everyone deserves to have their lead service line replaced, yet there are people who will likely struggle to afford this work. The goal of analyzing LSLR affordability is to assess where federal resources can have the greatest effect on household-level affordability.

That concern for households translates directly into a concern for the communities that households live in, and this is for a couple reasons. First, since local units of government and utilities will in many instances pay for part or all of a lead service line replacement, they may indirectly ask households to pay for replacement. Without regional, state, or federal funding, local units of government and their utilities will likely turn to residents to generate revenue. So household costs (and thus affordability) may be directly affected by community-level costs.

The second reason why communities will feature prominently is that federal funding for LSLR is distributed at the community scale. Federal lead service line replacement funding flows through the State Revolving Fund programs, which make funding available to water utilities. Thus determining how this funding can best influence LSLR affordability will mean thinking about where their application have the greatest potential to enhance affordability for households.

Two additional considerations are important to note:

- Scale of analysis (state). The concept of affordability below is meant to diagnose relative affordability across a state. This is because of the focus on prioritizing existing federal LSLR funds, which are distributed by states to their utilities.

- Relative affordability. The intent of this analysis is to assess relative affordability of LSLR among a state’s communities. The intent is not at this point to develop an absolute threshold beyond which LSLR is or is not affordable.

2) LSLR cost within a community (LSLR burden)

LSLR cost is the starting point for understanding LSLR affordability. For utilities and local units of government, LSLR cost is essentially the total cost of lead service line replacement within that geography. The two biggest variables for this total expense concern local per-unit cost and the number of lines to be replaced. Much has already been written about per-unit costs for replacement. And as communities inventory their service lines to comply with state and federal regulations, the number of LSLs will become more fully known.

For the purposes of understanding LSLR affordability, a much more pressing question is how these costs will be experienced by households. In the absence of grant funding from state or federal sources, local units of government and utilities will need to generate revenue for LSLR. The method of generating revenue will likely have a profound effect on LSLR affordability.

For example, if households within a geography are asked to pay directly for LSLR, the cost to residents can easily exceed $5,000. That cost will likely be unaffordable to households with strained financial capacities.

On the other hand, households may be asked to pay for a small portion of total community LSLR costs through locally-controlled revenue sources. These locally-controlled revenues may spread costs over a sufficiently large payer base and a sufficiently long timeframe to make the LSLR cost to households manageable.

There are a small handful of locally-controlled revenue sources that may have diverse effects on household affordability. It will be important to understand how these and any other available local revenues affect affordability within a community:

- Water rates

- General/corporate funds. Local units of government may be able to apply corporate funds to LSLR. This is not a revenue mechanism, but may be an available funding source some local governments pursue.

- Property taxes

- Special taxing and service districts. Local governments may have the authority to establish or leverage special taxing districts like Tax Increment Financing districts and Special Service Areas to pay for lead service line replacement.

- Sales taxes

- Other directly distributed federal grants. Local units of government may have access to additional federal funding sources that are eligible to be used for LSLR.

3) Additional community costs

LSLR cost is just one type of cost born by a community. LSLR affordability needs to account for this broader range of costs households face.

Here are some examples of costs that may be relevant:

- Housing costs. Housing is a major and pressing expense for households.

- Additional pollutants and environmental justice costs. When households experience compounding lead exposure through paint and soil, for example, their risk for lead exposure is higher. This carries significant lifetime health and intellectual development costs for affected or at-risk households. Other pollutants and environmental hazards may need to be considered, such as flooding incidence and air pollution.

- Utility bills. Average water bill and energy bill costs are a part of regular expenses for many households.

- Additional taxes and fees. Local units of government structure taxes and fees on residents, including sales taxes, property taxes, and registration and permitting fees.

- Additional infrastructure costs. Utilities and local units of government face additional infrastructure costs like sidewalk repair, water main replacement, and water treatment plant upgrades.

When evaluating these and other costs, a few key considerations include:

- Relevance. It will be important to determine how relevant a given cost is to LSLR affordability. For example at the local government scale, transportation construction projects that draw primarily on dedicated state or federal funds aren’t as relevant as a water main replacement – which may draw directly on water rates for funding. The point is to measure the aggregate of costs experienced by local governments and their utilities insofar as those relate to LSLR affordability.

- Scale of stakeholder. Costs will vary based on stakeholder. At the household scale, groceries, utility bills, and state and local sales taxes are all ultimately experienced as part of an aggregate cost of living. Whether or not a LSLR is affordable depends on that aggregate.

- The relative weight of each of cost. For example, housing costs should be weighted heavily, as shelter is often the first bill to be prioritized by households. As sociologist Matthew Desmond put it: “the rent eats first.” Utility bills (including water) also should likely be weighted heavily, as nonpayment can lead to disconnection that can be extraordinarily punitive for households.

4) Community capacity to generate revenue for LSLR

By “community capacity,” I mean the ability for a community to bear costs associated with LSLR. This is often measured in terms of median household income, which provides one important metric of capacity. Yet median household income fails to account for, for example, regional variations in cost of living and income diversity within a community, which are relevant factors in LSLR affordability.

Additional indicators of capacity could include:

- LSL percentage. Communities with a lower percentage of LSLs will have a greater capacity to generate revenue to replace those LSLs, as the cost can potentially be spread across the system. This will vary greatly depending on additional capacity measures listed below.

- Comprehensive indicators like the Social Vulnerability Index, which measures not just income but community resilience in the face of shocks.

- Income diversity. Income diverse communities may have a greater capacity to generate revenues in ways that are affordable to all residents (ie progressive revenues).

- Community size. Community size may influence the ability to access different kinds of financing instruments and thus reduce or spread out costs.

- Property characteristics within a community. Different types of property mix – residential, commercial, industrial, government-owned – within a community will change the quantity and type of revenue that may be generated through different types of revenue mechanisms.

One important note: determining community capacity would require careful consideration of the scale of a community. Large, income-diverse communities may have a significant population of financially constrained households. LSLR affordability needs to account for how those residents are asked to pay for LSLR.

5) Effect of state distribution of federal funding on LSLR affordability

The final element I’ll discuss is the influence of federal Bipartisan Infrastructure Law funding on LSLR affordability. This is the policy question I opened with, and it serves as the second intervention into LSLR affordability (municipal revenues being the first).

In analyzing how state-controlled federal LSLR dollars would affect LSLR affordability, the type of funding deployed would need to be further disaggregated:

- Additional subsidization. By federal law, 49% of the federal lead service line replacement dollars available through the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law must be made available as additional subsidization. This additional subsidization effectively does not need to be repaid. It is the most desirable kind of assistance to communities, and will be the most important type of funding to determine the effect on LSLR affordability.

- Loans. By federal law, up to 51% of the federal Bipartisan Infrastructure Law LSLR funding is available as low-interest loans to communities. Any loans must be repaid according to state-specific terms and interest rates.

- Set-Asides. Up to 31% of BIL LSLR funds may be taken as set-asides (see p. 22). Set-asides typically provide technical assistance to help utilities with LSLR planning and engineering, but may also be used to assist with other activities that could reduce LSLR construction costs. For instance, USEPA states that set-asides may fund “staff and contractors to work on LSLR education and outreach.” Outreach and education can increase resident participation in block-level replacements and thereby drive down replacement costs.

Understanding the effect of BIL LSLR funding on LSLR affordability would account for how differently situated communities, with their varying costs and capacities, would benefit from these different kinds of funding.

Conclusion

As the federal Lead and Copper Rule Improvements appear poised to require utilities nationwide to replace lead service lines, it will be critical for states to have tools available to prioritize available resources for utilities and households that most need assistance. LSLR affordability should be the first tool states deploy in determining that need.

As I outline above, LSLR affordability should be assessed comprehensively as an interconnected ecosystem of costs and capacities. This is an admittedly complex undertaking, and I have offered only a beginning of a framework for it.

While this undertaking is complex, it deserves sustained empirical and modelling attention. The implications of modelling LSLR affordability would be potentially profound: understanding where the greatest LSLR affordability burden is would allow state governments and policymakers to assess how to best address that need.

This blog offers additional perspective on a topic discussed at a January 2024 convening jointly organized by The Joyce Foundation and the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago to identify key information and research needs that, if met, could help communities overcome economic and financial challenges to implementing lead service line replacement projects. A summary of the convening is available in a Chicago Fed Insights article.