Yesterday’s Zoning: Prologis and Amazon Open a Warehouse on the South Branch in Bridgeport

This is the fourth part in a series about yesterday’s policies, today’s challenges, and tomorrow’s opportunities. Follow the links to read parts one, two, and three.

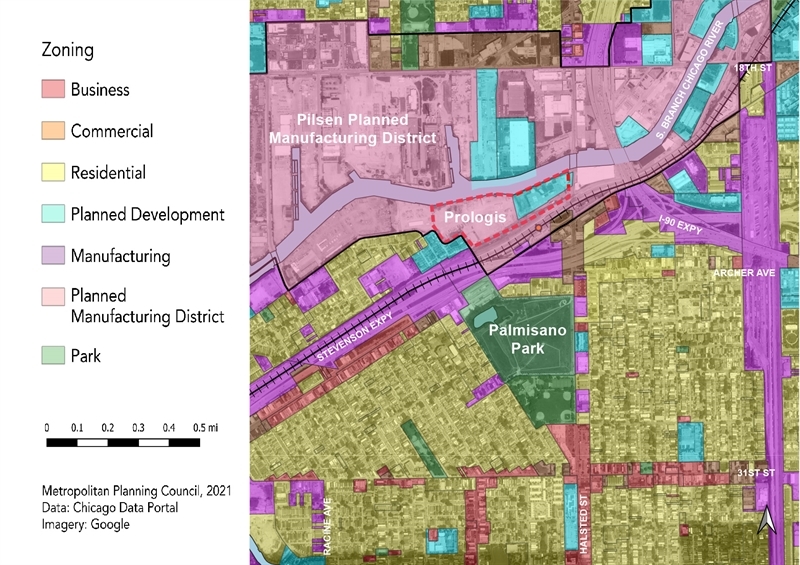

On the banks of the South Branch of the Chicago River, Prologis is wrapping up construction on a warehouse that will be leased by Amazon for use as a “last mile” facility. Located within the Pilsen Industrial Corridor, the recently constructed facility will include a 112,000 square foot warehouse, 16 loading docks, nearly 500 parking spaces, and 1,900 feet of publicly accessible river walk as required by the Chicago River Design Guidelines. The project was approved by city officials in late 2020 despite pushback from area residents, community organizations, and environmental groups.

How did we get here? The story of how another commercial development arose along the South Branch of the Chicago River.

Long-Inactive Land and Ignored Community Requests

One of the two parcels that is becoming the new Amazon distribution center was a former location of Crowley’s Yacht Yard. The yacht yard had been inactive for several years and seeing the trends of park amenities and residential developments (i.e. Eleanor St. Boathouse and adjacent homes) being built, the owner was interested in the idea of a mixed-use development, including residential. However, such a development would have required rezoning, as the parcel is part of the Pilsen Industrial Corridor. Despite informal requests as early as 2017 from the owner, MPC, and community organizations to consider rezoning or reassessing this parcel’s inclusion in the Pilsen Industrial Corridor, the Department of Planning and Development (DPD) would not assess the parcel outside of a then-proposed review of the entire Pilsen Industrial Corridor, as part of its Industrial Corridor Modernization Process. This process still has yet to be completed.

Eventually, Prologis bought the former yacht yard, as well as the adjacent parcel, the former site of Chicago Helicopter Experience. The second parcel needed to be rezoned in order to allow for a warehouse, which triggered the project’s compliance with the Chicago River Design Guidelines and approval from the Chicago Plan Commission. Otherwise, the project may have moved forward without additional public review.

Behind-the-scenes planning and resident objections

According to the timeline in Prologis’ proposal, the project was first shared with the alderperson and DPD a full year before any community meetings were held (Summer 2020). When projects are shared publicly at such a late stage, it can result in an engagement process that limits opportunities for meaningful incorporation of and revision based on community input. This type of community engagement is more about “presenting” and less about “engaging and listening,” which often occurs with new development based on the existing procedures of applying Chicago’s zoning code.

Community engagement in name only has become a pattern for new development, abetted by the structure of Chicago’s zoning code and procedures.

Prior to the warehouse’s approval in November 2020, a number of residents, community groups, and environmental organizations (including MPC) voiced their opposition to the project. Feedback was gathered through two community meetings and limited public input opportunities during Plan Commission and City Council votes.

Opponents listed a number of concerns about the proposed warehouse related to the increased vehicle traffic including unsafe traffic patterns for cyclists and pedestrians and increased exhaust and diesel fumes in an area of the city that is already in need of environmental justice reforms. The proposal from Prologis and project proponents touted the potential to create 200 much-needed new jobs, but community organizers noted that those jobs were not guaranteed and that there is no requirement for Amazon to ensure high quality, high paying jobs if the warehouse were to gain approval. Residents also were concerned about the viability of the publicly accessible riverwalk calling it a ‘river walk to nowhere’ and ‘greenwashing the proposal’ noting that it is the minimum required for new development adjacent to the river and in fact not in response to resident feedback as presented by the development team. Community members were also concerned that the developer and alderman’s office had failed to engage with and incorporate community-based river-oriented visions, such as the South Branch Park Advisory Council’s South Branch Parks Framework Plan (2019).

A rare close Plan Commission vote and ultimate approval

The project survived a close 8-6 vote during the November 2020 Plan Commission hearing. The tight margin was unusual (for context, Chicago Plan Commission votes are rarely so close, and projects are almost never rejected). At the meeting, chairwoman Teresa Cordova and Planning Commissioner Maurice Cox digressed beyond the proposal’s boundaries and expressed their views over the need to regulate the placement of logistics facilities in Chicago, with the chairwoman noting that most facilities are located on the South and West sides. Likely, the vote was so close due to the mobilization of residents, Bridgeport community groups, and others speaking at the meeting.

Ultimately, a rare tight Plan Commission vote would be the only hurdle the proposal would face during the city approval process. The proposal sailed through the zoning committee later that month and won full approval by the end of 2020. After the zoning committee approval, a number of aldermen and city officials expressed their excitement at another logistics facility in Chicago calling the warehouse a “big win,” “a wonderful project” and “a great project that’s going to bring some more badly needed jobs to the South Side”.

Outdated zoning fails to adapt to changing land uses

The Prologis and Amazon warehouse site is located on formerly industrial land that directly abuts residential land use to the west, the Chicago River to the North, and is within walking distance of the Halsted Orange Line Station. Some planning efforts have noted that vacant industrial parcels could be repurposed to better serve community residents and businesses. The Department of Planning and Development and other organizations have supported Equitable Transit-Oriented Development (eTOD) which promotes affordable and accessible mixed-use development near public transportation. The entirety of the new warehouse site is located within a five-minute walk of the Halsted Orange Line Station and directly connected to the heavily used Halsted bike lane. Community plans, including Our Great Rivers, have highlighted the potential for eTOD and mixed-use development on similar sites as future community assets.

The warehouse is within the existing Pilsen Industrial Corridor and complies with design standards in the Chicago River Design Guidelines. The developer’s plan appears to embrace creating public access at the site and meets the letter of relevant land use guidelines. However, the City’s repeated approval of warehouses on riverfront sites raises broader concerns about a lack of proactive, consistent, and whole-neighborhood-based planning that is failing to unlock valuable riverfront land for more river-conscious, transit-oriented, and community-supported uses.

Missed opportunities and potential for change

The Prologis warehouse case highlights the need for proactive change to city policy and zoning codes. In addition, it underscores the need for the City to be prepared with community-vetted ideas for where new and moving industries can be sited, and to proactively track and plan for precious riverfront land.

The Prologis warehouse demonstrates how landowners and commercial users benefit from Chicago’s relaxed and outdated development regulations and procedures

As with the previous posts in this series, MAT Asphalt and Cougle Foods, the Chicago Zoning Code not only allows for industrial uses next to rivers, parks, and residential areas but encourages them. Prologis, Amazon, and city officials are not necessarily bad actors, they are simply working within existing rules and frameworks. The Prologis warehouse demonstrates how landowners and commercial users benefit from Chicago’s relaxed and outdated development regulations and procedures, and how the lack of comprehensive zoning code updates that include considerations for equity, sustainability, and public health continue to fall short of balancing the needs of commercial land users and community residents.

Stay tuned for part five as MPC takes a deeper dive into the flaws of industrial land development in Chicago. We will review lessons that can be learned, how those lessons can be applied to the new citywide planning process, We Will Chicago, and demonstrate opportunities for equitable, responsive dialogue between developers, communities, and the City of Chicago to prosper.

For more in-depth background information on the Prologis approval process and the larger fight over industrial development on the south side check out this article from South Side Daily by Amy Qin.