Innovative Infrastructure Delivery: Chicago Parking Meter Analysis

Renegotiation of parking meter deal saves money and sets stage for future turnaround.

Executive Summary

The Metropolitan Planning Council (MPC) analyzed the 2013 Chicago parking meter concession renegotiation and found that the settlement will save the City of Chicago and taxpayers $1 billion. With further optimizations, the City can reduce or eliminate its quarterly payments to the private operator, or perhaps even return to a net positive revenue flow. This parking meter revenue should be invested in neighborhood-level transportation infrastructure: sidewalk, street and transit improvements.

Chicago’s 75-year $1.15 billion privatization of the city’s parking meters in 2008 was the nation’s first private concession for a publicly owned on-street metered parking system. From the perspective of the city and its taxpayers, the initial 2008 deal is widely regarded as a failure. All proceeds were spent up front as a one-time budget plug, not investment in infrastructure and neighborhood improvements with lasting benefits. Also, for the first few years of the concession, the City regularly owed the private operator millions of dollars in “true-up payments.” In 2013, the City took steps to reduce these costs over the remaining 70 years of the concession. After examining the initial deal and the 2013 renegotiation, MPC’s major findings and recommendations include:

The renegotiation will save taxpayers $1 billion. The 2013 agreement that the City of Chicago negotiated with private concessionaire Chicago Parking Meters LLC (CPM) will save taxpayers $25 million each year, or more than $1 billion in today’s dollars over the remainder of the contract.

The City must continue to fight fraudulent use of disabled parking placards. Beyond being illegal, abuse of disabled parking has major financial implications: In the first four years of the concession, people who fraudulently used disabled placards to park for free in metered spaces cost City taxpayers $73 million. Placards were so widely abused that in one year, a truly astonishing number—more than 90 percent—of people parking on Loop streets did so with a disabled placard, compared with the six percent allowed. Monthly sting operations by police have found that one in five people parking with disabled placards are doing so illegally.

With certain optimizations, the City could once again earn regular revenue from parking meters.

The City has taken steps to stop this abuse, including working with the Illinois General Assembly on legislation to limit free metered parking to those who are permanently disabled and not able to ambulate to or operate a meter. Further, the City must work with doctors to educate them about who truly qualifies, and crack down on doctors that issue placards to unqualified people.

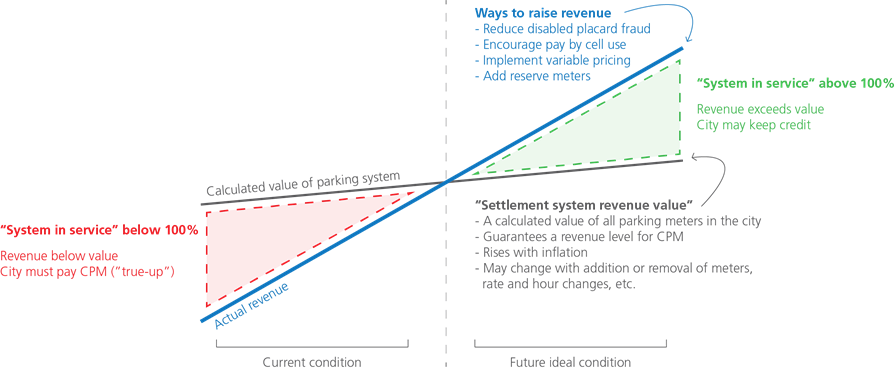

Maximize the system and earn revenue to invest in neighborhood improvements. The deal establishes a hypothetical amount of revenue that CPM, the private concessionaire, will earn every quarter. If the actual revenue exceeds that level, the City may benefit and even earn revenue. MPC recommends this revenue be spent on neighborhood-level transportation infrastructure: sidewalk, street and transit improvements. If neighborhoods directly benefit from parking meter revenues, Chicagoans’ perspectives on the meters might begin to change.

The concession requires that the value of the metered parking system be recalculated regularly as changes are made. If the value of the system decreases due to City actions, it owes CPM for the loss of value. If the value of the system is enhanced, CPM owes the City that credit. To date, the City has ended up owing CPM in this settlement, called the “true-up payment.” Clearly, the goal is to reverse that trend over the next 70 years. The City has already taken important steps to reduce those payments, including collecting revenue from private contractors that block meters during construction and utility projects. In 2013, this alone was worth more than $2.6 million.

While these revenues have helped, the City could avoid paying any true-up at all if it were to reach 100 percent “system in service” (excluding any inevitable temporary closures). The day the 2008 contract was signed, system in service was 100 percent. Since that day, the city has never hit 100 percent system in service—currently it is around 95 percent. Under the contract, the City must annually increase meter rates by inflation. If it fails to do so, it’s on the hook. It’s also on the hook for any permanent changes to concession meters that reduce their value.

If the City brought system in service to 100 percent, it then would have greater latitude to pilot best parking practices, such as performance pricing initiatives, with less budget risk. There are a number of ways to generate the additional revenue necessary to reach or exceed 100 percent system in service. Examples include:

Strategically place new meters where demand is high. Reinstating 2,451 paid metered spaces on Sundays in Bucktown and Lakeview not only will bring in an additional $1 million each year, it will support small businesses by encouraging parking turnover. Consider this: Even parts of the Loop—the city’s most in-demand parking area—remain unmetered. Adding meters to a single block, 2800 S. Wabash Ave., reduces the City’s payment to CPM by $55,000 each year. The City should evaluate parking demand in all commercial areas to determine where new meters make sense until the revenue generated at those meters is adequate to meet the 100 percent system in service goal, reducing or eliminating the true-up payment.

In a pilot project MPC and Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning (CMAP) conducted in the Wicker Park-Bucktown neighborhood, we found some sections of the retail corridor had free parking including Damen, Armitage, Division, Ashland and Western. On streets with many destinations and high retail activity, the free parking is often used not by customers, but rather by residents and employees who park their cars for extended periods of time, sometimes all day. This was evidenced in the turnover survey on Division Street between Ashland and Damen, where about half the area surveyed is metered and half is free. None of the cars in the metered spaces stayed longer than three hours, while most of the cars in the free spaces stayed for at least three hours, and 17 cars were parked for the entire seven-hour duration of the survey. In this way, the free parking is damaging to local businesses whose customers struggle to find a parking spot near their destination. Areas like these retail corridors across the city are prime spaces for reserve meters, benefiting the city and local businesses.

Reserve meters. Under the concession, CPM operates two types of metered parking spaces: reserve and concession. The City retains 85 percent of the revenues from reserve meters (CPM takes an operating expense of 15 percent), and CPM receives all of the revenues from concession meters. Once the City has added enough concession meters and made other optimizations to reach 100 percent system in service, any new meters should be reserve meters, as this would allow the City to keep 85 percent of the revenue. MPC recommends using that revenue for neighborhood improvements.

Performance pricing. The concession allows the City to institute performance pricing, or variable pricing, on a neighborhood level. Performance pricing bases the hourly cost of parking at a meter on current demand for that space, rather than on an arbitrary flat rate. While there is potential risk—the City would be required to pay CPM the difference if revenues were to decrease—there is also potential reward: Parking is available so drivers can quickly find open spaces, resulting in less congestion and the City could capture additional revenues if they increase. Results of the 2013 study by MPC and CMAP suggest that, in Wicker Park and Bucktown, current parking rates are set slightly higher than daytime shoppers and visitors are willing to pay and slightly lower than evening and weekend visitors are willing to pay. The MPC-CMAP study recommends fluctuating the price for parking based on demand at different times of the day and week. This change could generate more revenue for the system by drawing more people to the area and balancing demand on weekends. Once other optimizations have been made to increase revenue and mitigate the risk of loss, the City should experiment with performance pricing.

Mobile pay. The 2013 renegotiation required Chicago Parking Meters LLC (CPM) to offer motorists the option to pay via a cellphone application. The City could earn money from mobile pay, as it retains any revenue generated from the service beyond $2 million annually. The more drivers switch from using cash or credit cards at the pay box to paying through the app, the better it is for the City. Current meter revenues suggest that only a small percentage of transactions would need to use mobile pay to meet the $2 million mark.

The City should retain experts in public-private partnerships. Public-private partnership deals are highly complex. The 2013 renegotiation—and its benefits to taxpayers—were possible because the mayor’s office employs experts with the skills and capacity to analyze these complex agreements and weigh their risks and value to the public. It is imperative for the City to retain and expand its expertise in public-private partnerships to protect the public when considering such deals. Some P3s even have provisions that require the private entity to provide an on-going dedicated revenue stream to keep expertise on staff.

2008: The initial agreement

Public-private partnerships

For the right project, public-private partnerships are a viable financing option. While the demand for better roads, transit, schools, and water and sewer systems continues to grow, tax revenues have not kept pace with inflation. Most taxpayers agree they want their elected officials to invest in infrastructure, but they do not want to raise additional revenues to pay for those investments. Public-private partnerships can address aging infrastructure problems and constrained budgets, deliver projects sooner and encourage innovation. Well-negotiated and written agreements are critical: They can create incentives for efficiencies and shift risk to private investors, who can bear responsibility for cost overruns or revenue shortfalls. At the same time, it is important that potential investments are chosen based on their ability to generate much-needed economic growth, improve our global competitiveness and promote community livability and sustainability.

While many have written off the Chicago parking meter concession a failed public-private partnership, that’s not entirely true. The failure was in the City’s short-term view of success—a large cash infusion—without consideration for the detrimental impacts on taxpayers over the next seven decades. The City solicited bids from the private sector for the most up-front money in order to plug short term budget holes and was willing to give up significant rights to the asset. Instead of making a long-term investment that would have generated economic returns, Chicago instead used the proceeds for a short-term budget fix.

The lesson learned is that all future public-private partnerships must be subject to an independent, third-party review to ensure the interests of the public are protected. Because public-private partnership deals are highly complex, there must be an independent body with the authority to review concession documents from a citizen’s perspective and look for inconsistencies between the agreement and current and future taxpayer needs. City Council also benefits from an independent report on the transaction’s parameters. Under Mayor Emanuel, such a process was used through the creation of the Midway Advisory Panel, which considered privatization of Midway Airport.

The Chicago parking meter concession agreement

On Tuesday, Dec. 2, 2008, Chicago Mayor Richard M. Daley unveiled a $1.156 billion bid that would hand over operations of the City’s 36,000 parking meter spaces to Chicago Parking Meters LLC (CPM), a private company led by Morgan Stanley. The following Thursday, City Council approved the 75-year deal in a 40 to 5 vote. In exchange for the up-front payment, CPM won the right to collect revenue from the parking meters for 75 years. In return, CPM was required to update the individual coin-operated meters to modern machines that offer non-cash alternatives and to maintain and operate the meters throughout the life of the contract. When the transaction closed in February 2009, the City received $1.151 billion from CPM, which at that time was owned by a consortium of Morgan Stanley, Allianz SE’s Allianz Capital Partners and the Abu Dhabi Investment Authority.

Under the concession, the City retained control of parking regulations, enforcement, fine collection and associated revenues, as well as meter rates and hours of operation, so-called “Reserved Powers.” However, the 2008 contract required an increase in hourly parking rates each of the first five years—regardless of occupancy rates—across the City, which for this purpose was divided into three designated zones.

Under the concession, CPM operates two types of metered parking spaces: reserve and concession. The City retains 85 percent of the revenues from reserve meters (CPM takes an operating expense of 15 percent), and CPM receives all of the revenues from concession meters. Almost all (some 97 percent) of the on-street parking meter spaces in the City are concession, and they are indistinguishable to the user from reserve. Per the agreement, the City may add reserve or concession meters to any non-metered street and can set whatever price the City chooses.

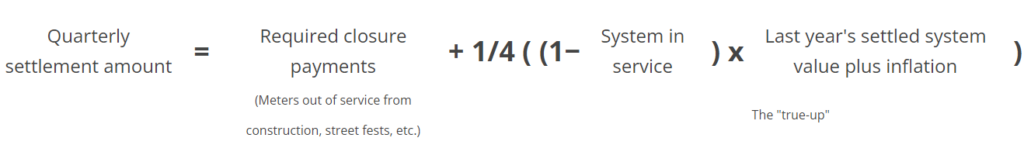

Quarterly settlement amount

A quarterly settlement amount is paid based on two data points: The true-up calculation based on “reserved power actions,” or permanent changes the City makes to concession meters, such as hours of operation or rates; and “required closures,” or temporary closures to concession meters, such as street construction, weather parking bans or neighborhood festivals.

Each concession meter has a revenue value, based on rates, hours of operation and utilization rate. Under the concession, the City agreed to annual rate increases for the first five years. After the first five years, if the City does not increase rates annually based on inflation and does not take any other actions to increase the potential revenue value of the metered parking system, the City would owe a true-up payment to CPM; the amount of the payment would depend on the actual usage of the system during the prior year. Any City-imposed changes that decrease this potential revenue (for example, rate changes or taking meters out of service for road construction) must also be reimbursed to CPM through the quarterly true-up payment.

So, while the City has the power to change metered parking rates and hours of operation—its reserved powers—if a given change results in a reduction of the system’s aggregate revenue, it is factored into the quarterly true-up calculation and may require the City to make a payment to CPM to match the lost value. Likewise, if the City takes actions that increase the potential revenue of the system (such as adding concession meters), the City captures that value and is left with a positive balance against any future true-up payments it owes. Changes to utilization of metered spaces due to City-imposed changes in rates (other than increases for inflation) or hours are measured in the year following the year in which the rate/hour changes are implemented. If utilization decreases, the City may owe a true-up payment; if utilization increases, the City may get a credit. The City has the potential to earn revenue in this process, as there is a verbal agreement that if the City built up a credit of $5 million or more, CPM would “cash the balance out” to the City.

If the City makes no changes to meters in a quarter and the demand for parking, along with the revenue generated at meters, goes down, the City isn’t on the hook for the revenue loss: CPM bears this risk.

2013: Renegotiating for savings

Dispute on true-up calculation

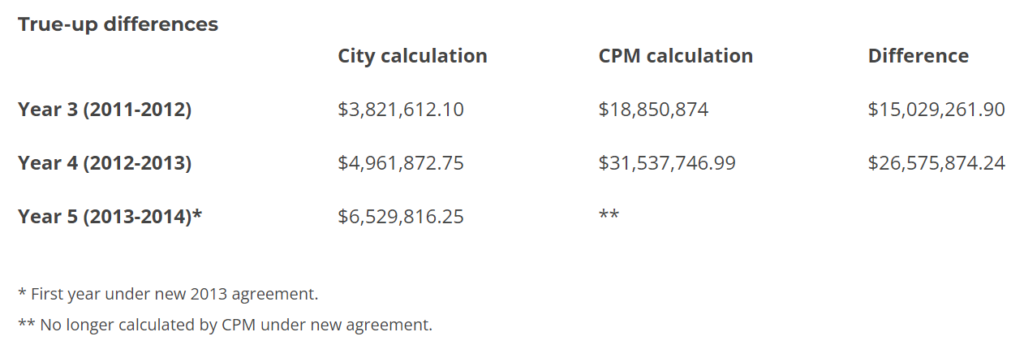

The true-up is calculated based on the previous years’ actions. If the City makes a change in year one of the concession agreement, the effect on utilization rates is measured over the course of year two, so any true-up payment resulting from a decrease in utilization is not invoiced until year three. Soon after Mayor Emanuel took office, the City received a true-up invoice calculated by CPM that showed a $4.5 million payment due for the first quarter of the 2011-2012 year, resulting in an expected total of $20 million for the entire year. The mayoral administration immediately questioned why it had to pay for changes made to some of the spaces. City staff calculated the true-up to be $3.8 million for the whole year, a more than $16 million difference.

The dispute centered on certain reserved power actions taken by the Daley administration during the first year of the concession to accommodate theater goers. A new two-hour meter time limit made it almost impossible to park legally while seeing a movie or a show. Aldermen, community groups and theater districts asked to have the period-of-stay at certain meters across the City changed from two to three hours to accommodate their patrons. Because the City is granted this authority under its reserved powers, it was able to make the change at 10,000 concession meters. Because the City only changed the period of stay and not the rate or hours of operation, it did not believe this action would affect the value of the meter system and therefore not be part of the true-up calculation.

This change happened at the same time that the meter rate quadrupled from $0.25/hour (pre-concession rates) to $1.00/hour (year one post-concession rates), as required by the concession agreement. Economic principles dictate that if the cost of a service is increased fourfold, the demand for it will go down. Fewer people are willing to pay $1.00/hour than $0.25/hour to park. However, the true-up was based on the utilization of the spaces when the price was set at $0.25/hour.

Because the City altered the 10,000 meters, CPM argued, the City would be on the hook in the true-up—not just that year, but the remaining 72 years of the deal—for any utilization decrease at those meters, regardless of what caused it, be it the hourly rate increase or the period of stay.

The Emanuel administration countered, arguing that changing the time limit had nothing to do with the demand for parking. Rather, the demand for parking decreased because the price increased. Under the concession agreement, the scheduled price increases should not result in any true-up payment being owed by the City, no matter how much usage of the metered spaces declined as a result.

This difference had major implications for the City’s budget. CPM’s true-up calculation would have charged the City $15 million more in 2011-2012 and $26.5 million more in 2012-2013.

That meant the City would owe about $25 million every year, an additional $1 billion over the life of the contract, in true-up payments. This money would have come directly out of the City’s corporate fund, which is used for basic services such as public safety and transportation.

2013 agreement

In April 2013, the City and CPM settled their differences on the true-up formula. CPM agreed to accept the City’s calculation of what was owed. Moving forward, it was agreed that the City would calculate the quarterly true-up payment and present it to CPM. In another important change, the City gained the right to the data on usage of the parking meters on a daily basis. The City Council approved the agreement on June 5, 2013, and both parties signed the agreement immediately thereafter.

The 2013 agreement also changed days and hours of metered parking enforcement. In the 2008 deal, parking remained free from 9 p.m. to 8 a.m. at all meters across the city. In the 2013 renegotiation, the City agreed to extend meter hours, from 9 p.m. until 10 p.m. in most areas, and until midnight on the Near North Side. In exchange, the revised deal included free parking on Sundays outside of the central business district, or the area north of Roosevelt Road, south of North Avenue and east of Halsted Street. It also required CPM to allow motorists to pay via a mobile app, although a “convenience fee” of 35 cents is applied to any purchase less than two hours and accounts must be set up with a minimum initial balance of $20. More importantly, the City could earn money from pay by cell, as it retains any revenue over $2 million generated per year from the service. CPM would make any necessary mobile app revenue payments to the City twice a year.

The newly free parking on Sundays caused concern in some retail areas, as prime parking spots could be occupied by drivers who park their car on Saturday evening and leave it until Monday morning for free. A handful of aldermen initially requested that Mayor Emanuel reinstate paid parking on Sundays in these retail areas that depend on parking turnover and availability. In April 2014, City Council passed such an ordinance, reinstating paid Sunday parking primarily in the 32nd and 44th wards: select retail corridors in Wicker Park, Bucktown, Lakeview and Wrigleyville. This shift away from free Sundays stands to generate additional revenues for the City, as much as $1 million in the first year. In another move to offset the true-up payment, the City began collecting revenue from private contractors during construction and utility projects for blocking off meters, which in 2013 totaled more than $2.6 million.

Overall, the renegotiation resulted in $2.1 million in savings to parkers, but that may be diminished if more neighborhoods ask to reinstate paid Sunday parking. The City also gained control of—and the revenue generated by—17 parking lots, but moved some reserve meter spaces to concession spaces in exchange.

How the quarterly settlement amount is calculated

Every year, CPM expects to earn a hypothetical amount of money, which the contract has calculated based on existing utilization and current meter rates and hours. This amount is adjusted on a quarterly basis through the true-up calculation: the amount the City might owe CPM in any given quarter for making changes to metered parking spaces. The true-up is based on the value of the system during the previous year (“settlement system revenue value”), an adjustment for inflation and a “system in service” ratio. Any payments for required temporary meter closures are also included.

Required closure payments are made any time the City takes a metered spot out of service temporarily. For example, if parking spaces are shut down for a street festival or road work, the City must reimburse CPM the full amount of the projected revenue value for those meters during that time period. The City receives an allowance of days for which a required closure can occur without having to make a payment— 8 percent annually in the Loop and 4 percent annually in neighborhoods. If the annual allowance is exceeded, any concession space closed for more than six hours in a day requires the City to pay CPM for the lost revenue from that space for the entire day.

System in service is a percentage that accounts for any changes the City may have made to the value of the system by exercising its reserved powers: changing rates or hours. If the City’s changes result in the value of the system improving, system in service rises. Conversely, any reserved power changes that result in a loss of value will decrease system in service. System in service was, by definition, 100 percent at the beginning of the concession. As of 2014, it is approximately 95 percent.

Consider a hypothetical quarter with 95 percent system in service. If the settled value of the system last year is $105 million, that becomes $107.1 million this year with two percent inflation. Five percent of that—the out of service portion— is $5.35 million annually, or $1.33 million for one quarter of true-up. Add in $250,000 of required closure payments, and the hypothetical quarterly settlement amount is $1.58 million.

Disabled placard abuse comes at a significant cost

Fraudulent use of disabled placards has cost more then $73 million over the past four years. Prior to 2014, Illinois state law allowed cars with disabled placards unlimited free parking. This resulted in widespread abuse of the system, particularly as the value of metered parking rose significantly. The City must reimburse CPM if the total revenue lost through use of concession spaces used by disabled drivers exceeds six percent of the total revenue from concession spaces for that year. CPM statistically samples the use of the system by cars with disabled placards on a quarterly basis and annually bills the City for any excess lost revenue. The City has paid about $73 million thus far for the excess lost revenue, which is largely attributed to abuse of the system, not legitimate use by disabled parkers.

The first disabled parking invoice resulted in a $12 million payment. The second and third year of invoices resulted in a payment of $42.9 million. CPM has recently invoiced the City $18 million for year four of the concession.

The mayor’s office initiated sting operations to thwart the abuse, and in 2013 worked with the Illinois General Assembly to enact Public Act 097-0845, which narrowed the use of disabled free parking placards. The law took effect Jan. 1, 2014. Forecasting based on an analysis of Q1 2014 shows annual payments may go down to as low as $1 to $2 million each year, but this could increase again if more drivers unlawfully obtain and use disabled placards. The first quarter survey (March, April and May) found that all zones except for the Loop had fallen below the six percent limit. The Loop was significantly down, from more than 90 percent to 17 percent. Subtracting the six percent allowance, the City must pay 11 percent, or $250,000, of the $2.3 million in meter revenue collected in the Loop for that quarter.

It is critical that the Illinois Secretary of State’s office, which administers the disabled parking placard program, continues to take every step to ensure drivers do not obtain or use disabled placards under false pretenses and that the state law is strictly enforced. Further, doctors must follow the rule change or face penalties if they continue to grant placards to patients that don’t qualify. The City is planning a new campaign to educate the doctors who approve these placards, to ensure only those residents who truly need disabled parking receive placards.

Implementing performance pricing

When on-street parking is priced too low, demand exceeds supply, resulting in drivers circling the block looking for a space. The result: clogged streets and air pollution. Up to 30 percent of traffic on commercial corridors is actually drivers looking for on-street parking. If all of the prime parking spaces are full all of the time, frustrated potential customers and visitors may give up on their trip to the neighborhood, ultimately hurting local businesses. Well-designed parking policies ensure the continued health and vibrancy of a neighborhood. When parking is priced correctly, most but not all of the spaces are full, leaving a space or two available per block to satisfy visitors’ needs.

MPC has been advocating for better parking policies in Chicago, including an analysis of on-street parking demand in busy commercial districts like Wicker Park. Partnering with the Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning and the Wicker Park Bucktown Chamber/Special Service Area #33, MPC recently completed an analysis on how performance pricing—charging different rates for parking based on shifts in demand at different times or days of the week—can achieve just the right number of available parking spots.

After surveying the demand at almost 12,000 parking spots in the Wicker Park-Bucktown (WPB) neighborhood, we found that the vast majority—almost 11,000—are not metered, but rather are free. For this reason, balancing the utilization of on-street metered parking through performance pricing is essential to address the supply and demand challenges. With most spaces in the area free, the price of $2.00 per hour seems extreme, and many drivers choose to spend time looking for a free space rather than pay. In WPB, this creates an unbalanced parking supply where the streets with the primary destinations have abundant parking availability during some hours of parking meter enforcement. This begins to change in the evenings, and especially on Friday and Saturday nights, when the parking is completely full. These findings suggest that current rates are set slightly higher than what daytime shoppers and visitors are willing to pay and lower than what evening and weekend visitors are willing to pay.

How to implement performance pricing

The concession allows the City to institute performance pricing by neighborhood. The process for a change in meter rates, additional locations or hours requires City Council to evaluate whether that change would have an adverse effect on overall parking meter revenues and to pass an ordinance. However, when the City makes any change to a meter, it comes with the risk of owing CPM in the quarterly True-Up if utilization decreases. The solution is getting the system in service to 100 percent and the True-Up payment down to $0 or even to a positive balance to mitigate the budget risk for taxpayers. This would create an opportunity to experiment with a performance pricing pilot, because the risk associated with the effect of changing meter rates to the system’s aggregate revenue would be limited.

If the City wishes to initiate performance pricing, CPM must install software to the multi-space meters that allows for this rate structure. The concession agreement requires that this software (Time Differential Metering Systems) must allow the City to set rates in increments as small as 15 minutes or as long as 24 hours. The software also must allow customers to purchase multiple hours of parking across varying rate schedules. The concession did include a provision that requires the software to allow customers to pay a reduced rate during a “non-peak” time, as an incentive to use a parking spot during periods of low demand. The software also must allow the City to either increase or decrease the rate for every subsequent hour that a customer purchases to park.

Conclusion

MPC is encouraged by the opportunities presented as a result of the City’s 2013 renegotiation with CPM, and strongly suggests the City continue to create opportunity within the legal confines of the concession agreement to better serve neighborhoods, businesses and taxpayers. Chicago has the opportunity to position its neighborhoods for future growth and prosperity, provided that the City continues to reduce the annual True-Up amount, enforce disabled parking and promote smart parking policies that appropriately generate revenue and manage demand.